Tom was a National Serviceman who served at 101 Signals Unit Brockzetel and lived

at RAF Jever. He went back with a visiting party of ex-101 Signallers in May 2008

and during the visit Tom told us that he had been a National Newspaper Editor,

a Lancashire Councillor (still is) and also edits a small local newspaper called

"The Idle Toad". Over the years Tom has written in the Idle Toad about his

experiences of National Service and he has kindly allowed us to reproduce three

of those articles here.

June 2005

Tom Sharratt tells the truth about National Service

SEVERAL of these so-called "reality" television shows over the past 12 months

or so have claimed to show what National Service was like.

They take a clutch of young lads and put them through military drill, discipline,

and barrack-room living and think it shows how today's lads would match up to their

grandfathers.

Believe me, nothing could be further from the truth. Kid gloves were not standard

issue for drill corporals when I was called up.

The idea of National Service -- yes, in my mind it still starts with capital letters --

was that the Government could make up numbers in the armed services by conscription.

Conscription? That means forcing every able-bodied person in the land that's not

female to join the armed forces for a fixed period. From 1947 to 1962 it was two years.

Though politicians didn't realise it at the time, the result was that Britain ended

up with a bunch of stroppy, unprofessional soldiers, sailors, and airmen whose only

interest in life was crossing off the dates on their demob charts. Fighting? Forget it.

It was two years of utter boredom and loneliness. It was also a time of hilarious

misadventures, a time when you formed friendships that would last you for the rest of your

life.

You never forget your service number. To this day, almost fifty years later, I still

identify myself as 5031420 when I phone my RAF comrades or write to them.

One friend in Nottingham invariably replies as 5031417 (he was three places ahead of

me in the queue when we joined up) and another, in Blackburn, always greets me with the

words GET SOME IN!

This is a service joke that no-one who hasn't been in the forces will ever understand.

It refers to the fact that he got his call-up five weeks before I did and I was therefore a

sprog, a lesser being in the order of creation who had not got as much service in as he had.

No, it's not funny, is it? I've never thought so, either.

Joining up meant RAF Cardington, a bleak camp somewhere in Bedfordshire. It was a

reception unit where you got your kit and your first service haircut.

Kit? If it fits, you hand it back. Haircut? Everything off. And you had to pay

for it too. The only other thing I remember about RAF Cardington is that it had the biggest

aircraft hangars in the world, where the R101 was built.

In the 1930s airships were thought to be the future of aviation. The R101 proved they

weren't. It crashed in France.

After Cardington, Bridgnorth. If you thought Cardington was bleak you hadn't seen

Bridgnorth.

RAF Bridgnorth was perched on a windswept ridge somewhere in Shropshire. It consisted

of vast squares of parade-ground tarmac and endless rows of wooden barrack huts. Here we

spent eight weeks of hell that were, as we later realised, the funniest in our lives.

Every minute was drill. We even had to march to the cookhouse, and marching is a risky

business if you don't know how to march.

The entire camp was laid out on a square grid pattern, and at every intersection there

was a giant water tank to provide an emergency supply in case any of the huts caught fire.

Each day a different victim was ordered to march the squad to the cookhouse, and one day

the poor sod who was put in charge hadn't a clue how to do it. He could manage

QUICK MARCH but after that he was lost.

So were we. At the first intersection there was no RIGHT WHEEL and three men were

in the water before we heard HALT.

Then there were pits. Pits are beds. Pits are where you try to spend most of your time.

One poor lad in my but was called Bill Beechey. Bill was a master skiver. He spent more

time in his pit than any of us.

But one day he came a cropper. As he lay in his pit, fast asleep, our drill corporal came

in. He spotted AC2 Beechey fast asleep. His eyes glinted with malicious glee.

Now Corporal -- well, even after all these years, I'd better not give his name -- was the

perfect military man. Toecaps that put a mirror to shame, trouser creases that could slice

hairs, and a cap with a slashed peak so vertical over his eyes that it would have brought tears

of envy to a regiment of guardsmen. His greatest skill was to pronounce corporal the army way

-- coprl, with a long o.

He crept silently -- yes, crept, in those big boots - up to Bill Beechey's bed and roared:

BEECHEY!

Something happened then that I have never witnessed since. I swear to this day that Bill

Beechey, still recumbent, rose vertically three feet from his bed in absolute shock. Poor Bill.

He was still a good skiver, though.

I draw a decent veil over the common indignities of basic training. Standing in a line and

being told to drop your underpants and cough is not, to my mind, worthy of record; nor is the gas

chamber -- stinging eyes and a sprint round the football pitch singing Davy Crockett -- or

bayonet practice. Bayonets? Airmen?

Then came the moment of glory: the passing-out parade. It is well named. One thing that

servicemen do on passing-out parade is pass out. Guardsmen do it regularly.

And there is one military crime that surpasses all else. It is called Dropping Your Weapon.

We were told endlessly that if we dropped our rifle we should go down with it, feigning

unconsciousness and being carted off by the medics.

And what did I do on passing-out parade? Yes, you've guessed.

But I didn't go down with it. I reckoned that nobody could spot one individual out of a

thousand in identical uniform, so I did the unmentionable: I bent down and picked it up.

Don't tell. Snowdrops - RAF police -- are still on the lookout for that anonymous AC2

of 1956.

The next step was trade training. I went to RAF Middle Wallop and was taught how to be

a fighter plotter. You've seen them in war films, pushing little numbers round a big map.

But when I reached my final destination, No. 101 Signals Unit in North Germany, they didn't

want fighter plotters -- they wanted radar operators. So I was retrained and then, naturally,

spent the rest of my service as a unit clerk.

The job consisted mostly of sending and receiving, piles of paper and arranging urgent

distant postings for randy airmen who'd got local girls pregnant.

Don't forget: we were the front line, defending the realm in the Cold War. I'll tell

you more about that next time.

December 2005

Learning How To Be Shouted At

IN JUNE the Idle Toad published Chapter 1 of the military memoirs

of 5031420 Aircraftman Second Class Sharratt, T. E., R.A.F. (retired),

which described the heroic misadventures of basic training during

National Service forty years ago. Here, in Chapter 2, he resumes the

happy tale.

IF THERE is one thing you have to get used to during basic training it is being

shouted at. You are shouted at morning, noon, and night. Not that you've done

anything wrong, anything to deserve being shouted at. It's just that those who

are your bosses like shouting.

I described in my last article how I ended up at Royal Air Force Bridgnorth,

the hellhole of Shropshire. It was there, to his intense delight, that Drill

Sergeant McDevil spotted a minuscule trace of shaving cream behind the lobe of

my left ear on the barrack square one freezing November morning in 1956. Morning?

At 6am it wasn't even dawn.

Drill Sergeant McDevil was from Glasgow. I do not know much about Glaswegians,

but I do know one thing for certain: all Glaswegians become drill sergeants in the RAF.

It was not enough to tell me simply that I had a trace of shaving soap behind

my left ear, nor was it enough to inform the rest of the innocent young lads standing

next in line on that frost-bitten barrack square. Oh, no -- standing there in the

bitter Shropshire wind, Drill Sergeant McDevil felt obliged to tell all of Glasgow.

And he did it very well.

If I'd had the choice, I'd have given up shaving then. If you can't shave

without leaving a trace of soap behind your ear, you're not fit to be in the Royal

Air Force.

So it was quite a surprise that after eight weeks, I qualified. Perhaps it

was my other skills.

Like sizing the squad. This was my favourite drill manoeuvre. The purpose

of sizing the squad is to put the tallest on the left and the shortest on the right,

with all the rest in between according to height.

The beauty of this was that at 6ft 2in I was the tallest in the squad, and -

yes, you've guessed -- the tallest in the squad has nothing to do. All he does

is stand still while the rest cavort and cartwheel around him. Standing still,

I felt ever so smug. They were all being shouted at, and I wasn't. It made a

change -- a big change.

After basic training, trade training. The RAF is very diligent about trade

training. Never mind these clumsy fools who Drop their Weapon on Passing-Out

Parade. Anyone can do that. But when it comes to trade training we want to put

men where they matter.

Like AC2 Oik. He was from the West Country, born and brought up in Yeovil.

An apprentice air fitter on helicopters. Knew how to build aircraft from

beginning to end. They made him a cook. Yes, really, they did.

And then there was AC2 Plod. Good at languages (spoke three), got a place

at Oxford, volunteered for the Russian course. No good: fighter plotter.

So you didn't end up where you'd be most use. Never mind your abilities:

you went where the RAF wanted you.

And then there were POMs. POM stands for Potential Officer Material.

Every intake had to provide POMs and they were chosen by the time- honoured

service method of You, You, and You.

It was awful. It was embarrassing. All your mates hated you. An

initial interview with the flight commander and then the station commander.

In the end, it was a relief to fail.

Next -- Life in a German bog: No. 101 Signals Unit, the British Empire's

last defiant bulwark against the threatening hordes from the East. Be patient.

Summer 2006

Shouting to get rid of the Russians

LAST YEAR, in a sensational literary scoop that left the

publishing world weeping with envy, the Idle Toad acquired

the exclusive worldwide rights to the military memoirs of

5031420 Aircraftman Second Class Sharratt, T. E., R.A.F.

(retired), whose heroic misadventures graced our pages

in June and December. Here, in a third extract, he describes

what happened when he was posted to the famous No. 101

Signals Unit, stationed in the middle of a North German bog.

WE HAD a cunning plot. The Royal Air Force needed radar stations,

ostensibly to keep an eye open for enemy aircraft heading west in vast

numbers across the Iron Curtain to destroy NATO but more often to find

its own fighters that had got lost. RAF fighter pilots tend to get lost

regularly.

The radar station I was sent to was called -- well, no, I'd better

not tell you its name. After all, I've signed the Official Secrets Act.

My lips are sealed.

It was buried deep in a North German bog, one of those endless,

dull brown expanses that fill in the spaces between German towns when

they aren't full of pine trees.

The cunning idea was that if the entire unit was buried and camouflaged

the Russians would never spot it.

Good idea. So it went down deep, all three storeys, and the guardroom

at the entrance was craftily disguised as a North German farmhouse. Yes,

you had to hand it to them: it looked just like a North German farmhouse.

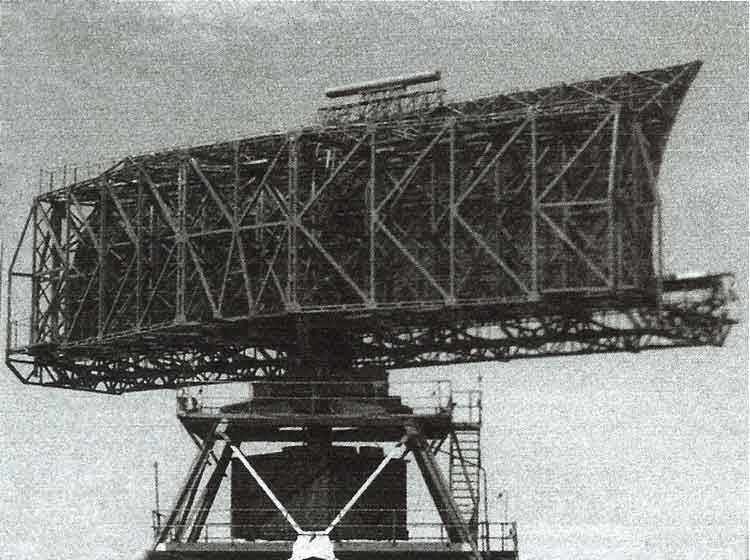

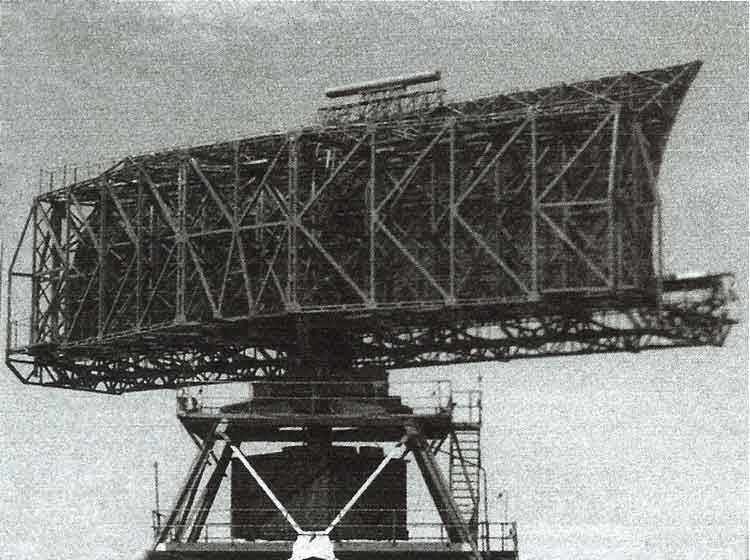

What worried me was the 100ft Type 80 radar dish revolving endlessly

in the farmyard...

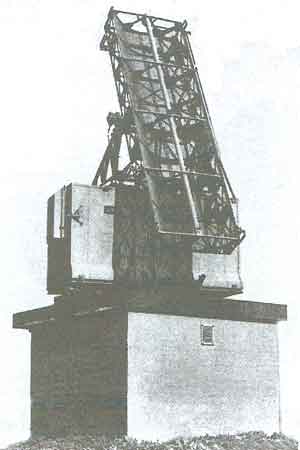

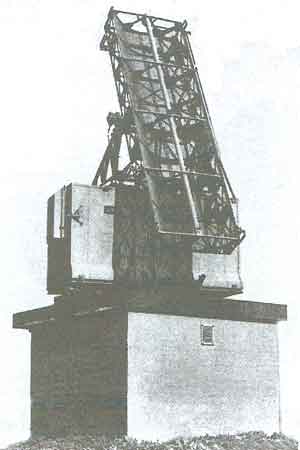

...and all those nodding Type 13 height-finding radars behind

it. Somehow, I felt they might be a giveaway.

The road didn't help much, either. In an effort to be co-operative,

the local German authorities had built a road to the site. It was over

two miles long and straight as an arrow pointing straight to the site.

Unfortunately it was made of white concrete. We were told you could see

it from the Kremlin.

There was something else that dented our confidence, too: Military

Missions. (Click to see a full description of these Missions.)

The Allies had an agreement with the Russians: you let us come

and look at your radar stations and we'll let you come and look at ours.

So every three months or so a dull green Volkswagen would turn up at

the front gate and three Russian officers would get out and start taking

pictures. We were given sten guns (but no ammunition) and told to shout

Dosvidanya.

I think this was supposed to frighten them away but it never did.

They took all their pictures and hopped back into the Beetle and disappeared

up the road until next time. I rather envied them their job -- it seemed

a right cushy number.