| 2nd TAF Blues by Mick Davis |

|

2nd T.A.F. Blues .

(Song) "Oh, I don't want no more of Air Force life,

gee ma, I want to go, but they won't let me go,

gee ma, I want to go home."

Back in the 1950s, in one of the coldest periods of the cold war, when NATO and

Warsaw Pact forces were huffing and puffing at one another from opposite sides of the

iron curtain, the men of 101 Signals Unit, Royal Air Force station Brockzetel - one of

a series of NATO radar units along the borders of western Europe - maintained a

round-the-clock watchful eye on the air movements of the communist bloc forces in

their allotted control sector. Together with a number of NATO radio monitoring stations

they were effectively what western political commentators liked to term, the 'eyes and

ears of the 'Free World'.

This was the decade during which political ideology seemed to boil down to a

simple choice of who was your favourite uncle.

Was it to be Russia's Uncle Joe, or America's Uncle Sam? These were the two

main political rivals on the world scene. Communism or capitalism - just take your

pick of one or the other. Well at least that seemed to be the choice. I can't

remember Britain having any sort of contemporary avuncular figurehead other perhaps

than Prime Minister "You've never had it so good" Harold 'Super Mac' Macmillan.

However, to be brutally honest at that particular juncture I couldn't have

cared less about political ideology. As a callow Royal Air Force Senior

Aircraftsman of late teenage years, my immediate priorities were, as I recall,

to indulge as often as possible in an excess of - and here I borrow a line from

a popular song of the era - 'Cigareets 'n' whusky 'n' wild, wild wimmin.' The

first two commodities were in plentiful supply but, to my great regret, the

wild, wild wimmin were all too frustratingly few on the ground.

Early in December of 1958, already having served a year in the signals

section at RAF Celle, near Hannover, followed by another at 2nd Tactical Ops

Centre at RAF Sundern near Gutersloh, I was posted to 101 Signals Unit

quartered at RAF Jever (pronounced, 'Yay-ver') in Friesland, north Germany.

Handed a rail warrant, I was shunted away in one of the unheated,

draughty rat-traps of a truck blessed with bone hard wooden-slatted seats

that served as a second-class railway carriage of the German Bundesbahn.

Dressed in full military rig, trussed like a Christmas turkey inside

an RAF greatcoat itself strapped over with a bewilderingly-complex system

of webbing accoutrements: heavy belt, various buckled shoulder straps,

mess tins, large and small webbing packs, the lot topped off with a huge

unwieldy canvas kitbag, thus it was - staggering under the weight of all

my worldly goods and chattels - I made my solitary way northwards.

After one of the coldest, most uncomfortable journeys of my young

life, I was met at Jever railway station by a churl of a Leading

Aircraftsman whose undeclared objective in life it soon transpired was

to paralyse with fear any innocent willing to step into his RAF

Volkswagen combi.

Depositing me - after a few truly heart-stopping, high-speed minutes

- outside the camp guardroom, his excoriating parting shot: "101 Signals

Unit? Hmmmph! Bunch of right bleedin' fairies they are, mate!" was my

cheery little introduction to RAF Jever.

Now before any newly arrived airman was allowed to commence official

duties at an RAF station, his first task was to get an 'arrivals card' -

more commonly known as, the 'blue card' - signed by the multiplicity of

heads of sections at his new station. These would include: station

headquarters; airman's mess; medical section, RAF police; sports section,

technical officer, etc., etc. This was done both for general

administrative and security purposes.

It was commonly expected the process would be completed within a day

at most. But for a dedicated skiver this was a task that could be strung

out for three or four days. However, for the truly experienced column-

dodger anything less than a week would be a contemptible failure.

For 101 S.U. personnel, the card had to be signed both at the main

camp and at Brockzetel, the radar site operated by 101 S.U., located some

20 miles distant. Ordinarily, this posting ought to have provided me

with a record-breaking skive, but for some inexplicable reason, (I must

have been sadly out-of-form that year) I'd gathered all the requisite

signatures in just three short days.

To make matters worse, my first visit to Brockzetel triggered a

small-scale security alert which, for a seasoned operator as myself

with a finely-tuned instinct for anonymity, was extremely unsettling.

Having caught the early morning bus taking airmen off to the radar

site which left from the airmen's mess, I spent the journey sourly

contemplating the prospects of working underground for the remaining

six months of my tour of duty in Germany, as the flat Friesland

countryside passed before my eyes until, after some 35 minutes I saw

in the distance a large, revolving concave radar aerial fronted by a

line of smaller see-saw type aerials set at an oblique angle. At this

point the airmen began to hang small security plaques from the buttons

of their battledress jacket pockets. I noticed each plaque displayed

a photograph of the holder below which in bold type was a number which

I (mistakenly) assumed was the last three digits of their service number.

As the heavy metal gates of the main compound were swung open by a

corporal service policeman the bus turned in and stopped opposite what

appeared to be a homely-looking bungalow.

Phil Riggott outside the 'homely-looking bungalow' during a recent visit back to the site.

Following the line of airmen into the bungalow, I found myself

in a brightly-lit security office manned by two or three SP's one of

whom held a clipboard and pen. As each airmen trooped past him they

called out a number which the SP recorded on his check sheet. Assuming

my companions were calling out the last three digits of their service

number I duly sang out my own last three, "640", and continued

following the line of airmen through the office and down a number of

flights of metal stairs which led into the very bowels of the earth.

Some two hours later, having gained the necessary 'blue card'

signatures, I returned to the surface and re-entered the security

office to find the place in a visible state of flux. This time

there were at least half-a-dozen 'SP's' milling about, of whom two

or three were brandishing sten guns.

Spotting my presence, a sergeant SP immediately bawled at me,

Where's your photo plaque, laddie?"

I explained to him that, as a new arrival who had been getting

his blue card signed, I hadn't yet been issued with one. My

explanation clearly failed to mollify him.

"And just how did you get in here without one?" he screamed into

my face. As I further explained that I had merely followed the other

airmen down into the unit, I rapidly surmised that I was digging

myself deeper into trouble as his eyes bulged ever wider and the colour

of his face changed from mottled red to deep mauve, which was when I

began to have the acutely discomforting notion that his anger would

only be assuaged when my brutally scourged body was swinging from the

nearest gibbet. (I think it worth explaining at this point that RAF

service policemen - known occasionally as 'Snowdrops' but more often

by the derogatory title of 'Snoops' - were not especially noted for

the quality of their intelligence. Indeed, it was popularly rumoured

that the IQ of the average snoop rarely exceeded his hat size, and if

it did so then never by more than a couple of points).

Fortunately, at this point, my position was rescued by the arrival

of a Squadron Leader who soon restored an air of calm and rationale to

the situation.

It transpired that the unit operated a security/safety system

rather like that of a coal mine, where a large board held a series

of individually numbered discs coloured black on one side, signifying

the holder as Out, and yellow on the reverse for In. As the board

held just 500 discs, when it came time for the SP to transfer the

number (640) I had given him from his written sheet to the disc board,

there had probably been some serious head-scratching before the penny

finally dropped that an 'intruder' had slipped in under the security net.

Rather than allowing the sergeant to charge me with some unspecified

misdemeanour, the Squadron Leader quietly suggested he direct his ire

towards the snoop who had allowed me to pass through into the unit

unchallenged. It had been, he concluded, a useful lesson for security

staff to absorb, learn from and, he added with deliberate emphasis,

must never repeat. Then he instructed me to make myself scarce in the

unit canteen until transport could be found to take me back to Jever.

2nd TAF Blues - Part II

For some must watch, while some must sleep: So runs the world away.

(Wm Shakespeare)

Whether by accident or design, the powers-that-be at RAF Jever chose to accommodate

the three hundred or so airmen of 101 SU - up to and including the rank of corporal

- in Block number 40, a building situated at the furthermost boundaries of the main

camp - a mere stone's throw from the airfield runway.

This was a three-storey H-block building erected during the 1930s, and although the

place could be described variously as, solid, dependable, durable and functional;

'attractive' was definitely one adjective that could never feature in the list.

Indeed, had it ever been aesthetically assessed, Block 40 would have been adjudged

a gloomy failure, to be ignominiously ranked just above the likes of, say, Spandau

prison.

However, for the next few months this was to be my home, and therefore my most

immediate task was to obtain a serviceable bed (in airman's slang: a 'pit'). This

meant a surreptitious recce so as to secure the combination of not just a decent,

well-sprung bed-frame - one whose springs were all properly connected, and not just

to the frame but, equally importantly, to each other - and a clean, firm mattress, not

the stained, saggy, well-used variety of dubious history whose qualities were guaranteed

to make you feel worse in the morning than you had been last thing at night.

Experience and cunning were required in this little enterprise. Where no readily

available decent quality example was on offer then it became a simple case of stealthy,

unobserved substitution where one 'relieved' another airman of his bed whilst he was

away on duty or on leave. (At one or two stations I served at during my ten years with

the RAF this practice was so endemic that prized beds and mattresses could circulate

almost as speedily as ugly rumours or dirty jokes.)

I'd found a vacancy in a pleasant three-man room at the end of a second-floor

corridor with a fine view of the airfield and beyond, which on initial inspection

appeared to be a good move, but on the morning after my very first busy night duty at

Brockzetel, extended by the thirty-five minute return bus journey to Jever, which left

me sorely in need of sleep, I was to discover I had dropped a clanger of considerable

dimension, for no sooner had my grateful head sunk on to the welcoming pillow and I had

blown a mental kiss towards the photograph of a pouting Brigitte Bardot sellotaped to

my locker, than the air was suddenly rent with the most ear-splitting, hellish crescendo.

Windows rattled, metal lockers and beds shook and appeared almost animatedly excited;

an empty mug on the bedside locker vibrated like a demented alarm clock, and the dead-tired

(in this instance, me) were raised to life as though shocked by a high-voltage charge..

Within milliseconds my feet were back on the floor.

The source of this dreadful racket was soon obvious. Staring out of the window I saw

a pair of Supermarine Swift aircraft hurtling into the sky from the end of the runway,

leaving in their wake a fiendish shimmering mixture of high-octane exhaust fumes in

concert with a hideous storm of decibels sufficient to cause milk to instantly curdle,

babies to cry, birds to turn to stone and fall to earth, and one dog-tired airman to feel

like kicking himself for being such an ignorant, short-sighted fool.

Curiously, before the end of the first week of night duties, I found myself able to

mentally shut out all intrusive aircraft noise - even the notoriously noisy Swifts - and

sleep the sleep of the righteous without any trouble whatsoever. - it was just a matter

of acclimatisation, and I count myself fortunate in being able to sleep anywhere (my wife

has long said that I'm the sort who could even sleep on a wire).

Pretty soon I'd settled comfortably into life in Block 40. The sheer variety of

interests and hobbies enjoyed by the disparate (and occasionally, desperate) characters

who inhabited the building rarely ceased to fascinate me.

They ranged from skilled model makers, photography buffs, radio and electronic

boffins who assembled a variety of clever and useful gadgets; there were artists;

musicians, amateur dramatics enthusiasts, language students etc. The list was long and

richly varied, we even had one character who grew rare cacti warmed by an infra-red lamp

all contained within a large spare locker.

A clear majority of Block 40 inhabitants were National Servicemen doing their obligatory

two years in the armed services. These were men from every corner of the British Isles, drawn

from all trades and professions who brought with them a wide variety of skills and talents.

Most were distinctly unhappy to have had their lives and careers interrupted by compulsory

military service. Many kept finely detailed 'demob charts' on which were hand-drawn,

multi-coloured calendars listing the remaining days and weeks to be served before demobilisation.

These charts were maintained with meticulous care, each day and week being ticked off with

ritualistic glee. It was very common to hear a 'demob-happy' airman calling out the precise

number of days and hours remaining until the great day of his release back to 'civvy street'.

Equally routinely, we regular airmen were subjected to merciless ribbing by the national

servicemen, and thus had to develop pretty thick skins to withstand a fusillade of provocative

questions such as, "Now, tell me, Mick - just how many more years have you got to do?" I had

a stock of well-rehearsed retorts including, "People have been me asking that old chestnut

since long before Pontius ever became a Pilate" or, if I was in a more aggressive frame of mind,

I'd make mischievous reference to the miserable pittance a national serviceman received in

weekly pay - which at that time was approximately thirty shillings (£1.50 in today's money) -

about two-thirds less than a regular airman's pay. "Don't spend it all at once when you get it

on pay day," I would add, twisting the proverbial knife in a little further, but mostly it was

just friendly banter.

We were paid every second week always on a Thursday in Block 40, in two group sessions -

the first bunch being those with surnames A to K followed by the L to Z's.

Pay day was eagerly awaited, and as the appointed hour drew near, airmen could become

noticeably excitable, and some went around muttering to anyone within earshot, "The golden

eagle flies today". (Though to be candid, 'flies' was not commonly the verb of choice).

A couple of tables covered with blankets and chairs were arranged in the large main entrance

hall for the visit of an accounts officer and two sergeants from station headquarters. We were

required to form orderly lines. When your name was called you would march a few paces forward,

call out the last three figures of your service number to confirm your identity, salute the pay

officer, at which his sergeant would consult the pay list and state the correct amount to be

handed over.

Payment was made in notes of military script, which in our case were British Armed Forces

Special Vouchers. The notes ranged through about seven different denominations all the way

from threepence to one pound, and were commonly referred to as, 'Baffs'.

Baffs were also exchanged for Deutschmarks at pay parade. The rate of exchange was then

a very handsome twelve DMs to one pound and six pence, and the DMs had to be pre-ordered. The

trick was to try to ensure you arranged for sufficient to cover the next fortnight's 'rest

and relaxation' away from the air base,

Usually, each pay day I would exchange somewhere between a third and a half of my wages

for Deutschmarks, and I was also putting away about 25 shillings a week in savings. Average

deductions from an airman's pay were then fairly minimal but at Jever I discovered there was

one punitive subtraction that was sadly all too frequently levied on each and every airman in

Block 40 and which came under the title of 'barrack damages'.

Every month a senior N.C.O. would make the rounds of the block checking every fixture and

fitting, noting each item that required renewal or replacement be it damaged or missing. This

could be something as small as a sink or bath plug, a light fitting, a broken window or other

damage to the structure of the building attributable to carelessness or general vandalism. The

cost of repair and replacement would be assessed; this amount was then divided by the number

of block residents before each airman had his share of barrack damages deducted from his

monthly pay.

At other RAF stations at which I'd served barrack damages were an intermittant nuisance

but at Jever they were as woefully predictable as, say, the outcome of a drunken weekend spent

in the Saint Pauli district of Hamburg - though it should be pointed out the latter activity

was costly in more ways than one.

Just who was responsible for barrack damages was something of a mystery though most of us

thought we knew who could be counted as being among the 'usual suspects'. The block's dustbins

were a regular target for abuse, and for a certain few of the block's inhabitants it had become

almost a tradition, when returning late at night, to carry the dustbins to the first floor

before hurling them over the landing railings with an accompanying cry of, 'Geronimo!' as the

bins made their crashing return to the ground floor..

But undoubtedly the most expensive month for barrack damages occurred after an incident

late one night when a crowd of 'tired and emotional' cooks (whose motto, as we shall see -

might have been, 'Through adversity to the stairwell'), and who lived on the upper floor of

Block 40 - returned home with the station sports' section's handcart in tow.

Dragging it through the main doors of the block and up the couple of flights of stairs

to the first floor landing presented them with little difficulty; it was only when they

attempted to manoeuvre it through the somewhat narrower entrance to the second floor

stairwell that the fundamental flaw in their plan became apparent.

At first all must have seemed possible, because the shafts and the front section of

the handcart passed comfortably through the doorway. However, the handcart's axle together

with its heavy hubs was marginally wider than the door frame and thus its upward journey

came to a sudden halt.

Sadly, the seemingly uncompromising resistance of the frame to the hubs failed to

register in the befuddled collective consciousness of this drink-fuelled crew and so they

persisted, and because this was a well-built - not to mention, very well-fed - group of

men, they persisted with considerable vigour to the point where the hubs became firmly

embedded in the door frame, but by now having completely exhausted themselves the cooks

finally conceded defeat and retired to bed.

In the following few days they made repeated attempts to extricate the handcart,

but their efforts were by now half-hearted and lacklustre and so, Excaliber-like, the

cart refused to budge and remained stuck fast there to mock them all until it was

officially discovered and orders given for it to be dismantled by a couple of M.T.-section

mechanics who severed the axle with an oxy-acetylene cutter.

[Special note: Readers of these memoirs may have seen an error in Part II, where I tell of

that the incident of the sports section handcart in Block 40. Having revisited Block 40 in

2010 it became obvious the incident could not have happened there. I apologise for this error.

(I now believe this took place at RAF Gutersloh later in my service). However, when I pointed

out the error to the C.O. of the Jever Steam Laundry website, Mick Ryan, he took the

sanguine view that as these jottings are mostly an attempt to give a general flavour of RAF

life from an ordinary 'erk's' perspective during those far-off days, it wasn't worth an

amendment.]

2nd TAF Blues - Part III

"...and the busy fret of that sharp-headed worm begins in the gross blackness

underneath." (Tennyson)

We all carry some form of personal emotional baggage around with us and I'm no exception.

In my case it has a name: nichtophobia.

At first glance this admission might suggest that I suffer from a morbid fear of German

girls saying "nicht", but you'd be wrong - though, sadly, if truth were told, had I a

deutschmark for each of those occasions a fraulein had replied in the negative to my

youthful, sweaty-palmed entreaties, I could have opened my own bank.

[During my stint at RAF Celle there was an enterprising young(ish) local Belle D'Nuit

who sold low-cost favours using a dark green VW Combi van as her mobile 'office'. At

weekends during the late hours, she would park the VW on one of the dimly-lit side

streets in the centre of town. However, the Celle civilian police frequently moved

her on, and thus her regular clientele could find locating her whereabouts to be tricky.

Her 'will-'o'-the-wisp' movements coupled with the fact she suffered from rather bad

acne prompted one very droll RAF station accounts clerk to dub her, "The harlot,

'Pimply' Nell".]

No, the simple fact is that nichtophobics are afraid of the dark, and thus the prospect

of working underground at Brockzetel represented the realisation of my worst fears.

For although 'the hole', as we termed the bunker, was illuminated as brightly as Hamburg's

Reeperbahn at weekends - albeit minus the attendant attractions of that once notorious

street - the very possibility, however remote, of a power failure pitching the place into

absolute blackness would fill me with an almost choking sense of dread each time the bus

turned into the Brockzetel compound, and it wasn't until I was in the signals traffic

office and focusing on the work in hand that I was able to suppress these irrational

thoughts.

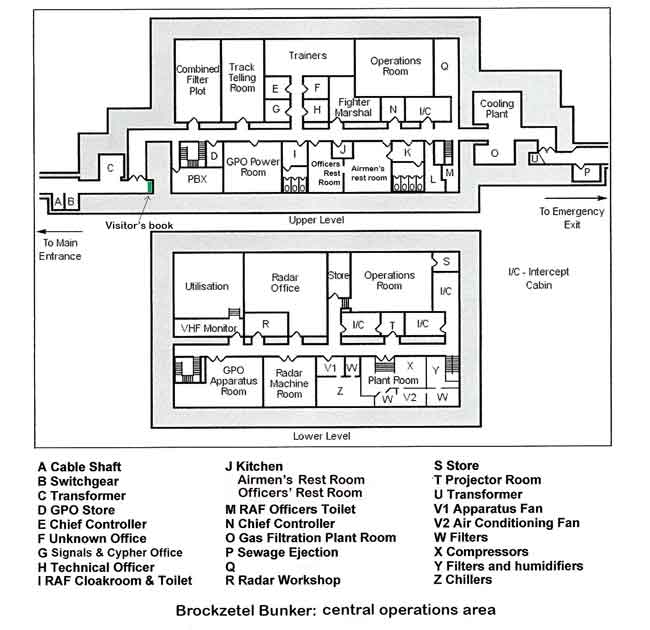

Main corridor in the lower level of the bunker.

As the weeks slipped away so too gradually did my fears as I found the bunker to

be more than adequately equipped to withstand a whole variety of system failures be

they naturally occurring or otherwise. In addition, I found that life as a 'mole' in

Brockzetel, though technically challenging, and on some occasions, mentally exhausting,

was in many respects quite enjoyable, for what also became apparent was that the working

atmosphere below ground was somewhat different from anything I had previously encountered

on other RAF units.

Discipline and order were always maintained but in a more relaxed, less formal way

than was usually the case. This was probably due in no small measure to the fact that

most of our officers were flying types who tended to treat their watch crews like

responsible adults, providing of course that an individual did his work conscientiously

and to the best of his abilities. This was in stark contrast to the attitude of so many

general RAF station administrative officers who all too often seemed to regard airmen

as a bunch of recalcitrant juveniles in need of constant chivvying.

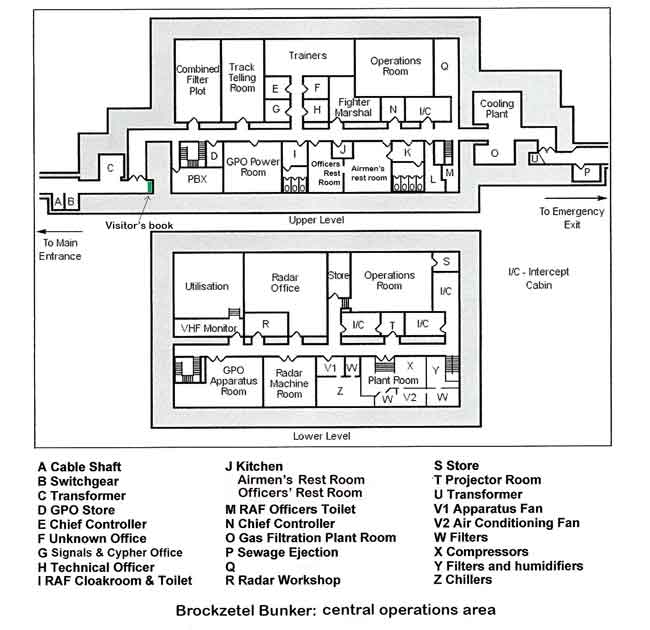

Our workplace, the signals traffic/cypher office was located through a sliding

door on the upper floor of the bunker, just off the main corridor. It wasn't very large,

about four metres square, a third of which was sectioned off by a three-quarter height

partition fitted with its own sliding door through which was the compact cypher office.

In here was a large safe and a full-length work bench on which sat two Type-X coding

machines. Cupboards under the bench contained various stationery items, rolls of tape

for the Type-X, message pads, etc. Both main and cypher office doors displayed warning

notices reading, Restricted Area: Authorised Personnel Only. The main area of the signals

office was equipped with eight Lorenz teleprinters and a tape perforator keyboard which

produced 5-unit Murray-code punched tape. There was also a small desk and a comfortable

armchair.

In daytime the department was manned by two telegraphist airmen, a teleprinter

mechanic and two cypher sergeants of whom Tony Willis was the senior and in overall

charge, but when the day shift ended at five in the afternoon staffing was down to

a single senior aircraftsman.

Hours of work in the bunker's signals office were almost as flexible as a female

contortionist with shift rotas frequently bent into such testing shapes it was possible

on the odd occasion to experience the weird illusion of seeing yourself coming in the

opposite direction.

With a full staff the standard shift rota was seven day (8am to 5pm) shifts followed by

two days off, seven evening shifts (5pm to 11pm) with two days off, and seven night shifts

(11pm to 8am) with three days off, but with leave and sickness frequently interrupting the

pattern sometimes it was necessary for us to work seven days on with a single day off,

followed by seven nights, from 5pm to 8am followed by just two days off. We had some minor

relief in that signals traffic airmen were not required to perform any secondary domestic

duties in the 'hole' for such was the pressure of work on our staff we could not have been

spared.

Juan for the road

Transport between Jever and Brockzetel for morning and late afternoon shift changes was

by bus, but at 11pm personnel shift transfers were usually limited to signals, the telephone

switchboard, and a corporal police dog-handler together with his canine companion, for which

an RAF VW Combi was used, driven by a green-uniformed, German GSO (German Service

Organisation), and most commonly by an individual whose first name was Otto, but who was

popularly known as 'Fangio'.

Where other GSO drivers took at least thirty-five to forty minutes for the transfer

journey, Fangio (who strove to emulate his Argentinian racing-driver hero) did it in thirty,

but given the lighter, faster combi, could comfortably shave a further five minutes off that

time.

However, on the 11pm changeovers, the drive to Brockzetel with Fangio at the wheel,

with forty-five minutes being commonly allowed for the journey, was, by long-established

custom and practice, interrupted at a certain juncture by what might euphemistically be

described as a 'refreshment stop.'

For after a kilometre or so following the turn-off from the main Jever-Aurich road on to

the minor road which led towards Brockzetel, at a certain point Fangio would brake sharply

and take a fast, lurching right-hand turn around to the rear of a dimly-lit Gasthaus where,

neatly and discreetly, he would park the combi in the shadows from where the five of us

would make an equally swift transition indoors.

I say, 'five of us' because, if our dog-handler happened to be a middle-aged 'Tyke'

corporal named Bert, his huge lion-maned, shambling, but extremely amiable German Shepherd

dog (whose name I've long forgotten) would always be first to arrive at the bar where it was

greeted as an old friend by all and sundry, and while we four humans enjoyed our glasses of

Jever pils the dog would slurp noisily from a tin bowl the entire contents of a large bottle

of Dunkel bier poured, at thoughtfully-timed intervals, by an attentive, dog-loving landlady.

"I only let him 'av Dunkel bier," Bert confided solemnly to me during my very first

'refreshment stop', "cos it seems to be good for 'is arthritis."

Over the course of a week's shift-changes we took it in turn to pay for the drinks, but

when on the fifth night, Bert indicated it was again the LAC telephonist's turn to pay he was

met with a shaking of the head before the lad said slyly, and very much tongue-in-cheek, "Oh,

no, don't look at me, Bert. We think it's the dog's turn to get 'em in."

"Ev you gone completely doolally?" replied Bert with heavy scorn before playing his

trump card, "...surely tha' knows t'dog dun't 'av any money,"

Had it ever been necessary, the elderly Bert and his friendly, arthritic,

semi-inebriated dog would have experienced real difficulties in preventing a determined

intruder breaking through Brockzetel's defences, but fortunately the security of the unit was

supplemented nightly by a couple of GSO's together with their Doberman Pinscher dogs and so,

to the best of my knowledge, no uninvited human being ever made it into the heavily-fenced

compound, though it was commonly rumoured that any unfortunate bird which might overfly the

fence to land on the large T80 aerial would be speedily 'microwaved' in minutes by the

aerial's powerful radio waves. However, never having been served roasted pigeon, partridge or

pheasant in Brockzetel's barely-equipped mess, I'm unable to confirm that particular story.

Stairwell to arms

What I can confirm is that the pace of work below ground rarely slackened until around

one in the morning when the teleprinters' mechanical chattering diminished and where I felt

able to relax. At this point I could collect a cup of coffee from the airmen's rest-room -

just a few strides from signals traffic - before sinking into the armchair and opening a book.

The 'Restricted Entry' notice on the exterior door meant that I was most unlikely to be

disturbed, but I was comfortable in my solitude and enjoyed the quiet hours until, once more,

the surrounding machinery rattled back into life.

Officially I was entitled to a meal break at 11pm in the unlovely 'shed' that was the

above-ground mess, but given that supper was an all-too-sadly predictable, grease-laden plate

of egg and chips, and that my break was commonly interrupted by a telephone call from 2 Group

Signals telling me there was a priority signal coming through requiring immediate attention,

there was little point making my way upstairs, and so it was that after a few short weeks

I no longer bothered.

Working the day shift was always something of a strain as signals spewed forth in a

never-ending paper torrent from the 'printers. Each signal had a clearly designated actionable

speed of delivery - marked in the message preamble - ranging from the lowly Deferred, through

Routine, on to Priority, Operational Immediate, and upward to the very rarely-used, Emergency

and the even more rarely-employed, Flash.

In my time at Brockzetel I never encountered a Flash message but we did have a couple of

Emergency signals whilst I was there, but given the high onus of responsibility carried by

our unit, this was about par for the course. A fair chunk of messages related to the aerial

activities in our sector by NATO's communist counterpart, the Warsaw Pact air forces, and

concerned the initiation of NATO's response to any anticipated threat we might face that

would be directed and controlled from Brockzetel. About ten per cent of messages were sent

in encrypted form and were often designated as 'Priority' or above.

These kept the two cypher sergeants gainfully employed throughout much of the day, but

at night message en/decryption became the responsibility of the Duty Cypher Officer - one of

the pair of commissioned officers who shared the responsibility of operations room controller,

and who, when first posted to the unit, was required to undergo two weeks intensive cypher

training under the tutelage of Sgt Willis and his companion in the small Cypher office.

Ordinary airmen in Signals Traffic were officially strictly forbidden to enter Cyphers

for none of us held the higher level of security-clearance required for this work. There was

a printed list of permitted personnel - regularly updated - attached to the inside of the

sliding door of the cypher office, and notices emphasising that entry rules be strictly

observed, but because none of the officers could type at speeds of more than a few words per

minute, an unspoken 'blind-eye principle' was employed in order to ensure the speedy

decryption of any coded message that required swift attention during the night hours.

And so, in practice, once having been handed the coded message, the Duty Cypher Officer

would firstly ascertain and enter the relevant settings for the Typex decoding machine before

discreetly and politely inviting the airman telegraphist to enter the small office and employ

his touch-typing skills to speed the decryption. Having finished the job it was customary

when the airman returned to his side of the divide, for the cypher officer to offer a quiet

word of thanks. They didn't have to do this but it was a courtesy rarely neglected, and it

was always pleasant to have our effort appreciated.

Had I ever been called upon to do the whole job of decryption it would probably not have

been far beyond my capabilities, as all conversation that took place in cyphers could clearly

be heard across in the signals traffic area, and thus within a month or so of my arrival, and

without any real mental effort on my part, I had absorbed - almost by a process of osmosis -

the greater part of the necessary technical procedures.

Shaken and stirred by a Martinet

There's a proverb that holds, Into each life a little rain must fall, but when early in

1959, a certain officer first showed his face in 'the hole', it felt as though a veritable -

if purely metaphysical - deluge had suddenly cascaded on all non-commissioned ranks, for once

Flight Lieutenant (let's call him, 'Martinet' because it has an appropriate ring to it)

entered our lives, it didn't take long for us to recognise that there wasn't going to be any

kind of handy ark in which we could seek refuge, for here was an officer who seemed to be on

a mission to shine a bright light into every nook and cranny throughout every level of the

bunker in order to correct what he perceived to be a pestilential plague of slovenly

behaviour and lack of positive service attitude.

Word soon filtered through to our office that Flt. Lt. Martinet was carrying out snap

inspections of his operations room watch crew as they debussed, with orders to get hair cut,

uniforms properly ironed and creased, badges polished, etc., etc. Any minor breach of

discipline and good order he encountered was dealt with the issue of a form 252

(disciplinary charge sheet) and before the end of his first week some half-dozen airmen had

been '2-5-2'd' by him for some kind of service misdemeanour.

He hadn't taken two strides through the door before we felt the measure of his zeal.

"Don't you stand to attention when an officer enters this room?" he barked, and even though

we were all busy handling signals traffic - which, ordinarily didn't require such a

reaction - we snapped dutifully upright.

"Right, now kindly inform Sergeant Willis that Flt. Lt. Martinet is here for cypher

training, he commanded coldly. Within a matter of twenty minutes or so he had 'corrected' both

cypher NCOs for some failure or other of procedural behaviour, and rarely a day passed during

his fortnight's training when he did not make some caustic criticism of Willis, his fellow

sergeant, and the signals staff. Everything in Flt Lt Martinet's world had to be procedurally

correct to the very last dotted 'i' and crossed 't' in the RAF rule book, but what he was

blissfully unaware of was that his absolute insistence on rules was soon to prove to be

something of an Achilles heel for him.

A week or so later, one afternoon as I arrived at 5pm for the first of seven extended

night duties, Tony Willis drew me aside to tell me that Flt. Lt. Martinet was listed as Duty

Cypher Officer for that night and watched my reactions carefully. When I smiled ruefully and

told him that I'd "stay on my toes", he nodded thoughtfully and said something about 'treading

with care', then said he'd see me in the morning and went to catch his bus.

Of miscues and mien

For many a long hour it appeared the night would pass without incident, but around 4am,

as I was absorbed in the exploits of the hero of a Louis Lamour western paperback novel as he

fought with a band of marauding injuns who were trying to make off with a rancher's innocent

daughter, (and why should it be, I've long pondered, that heroines in cheap cowboy novels were

invariably portrayed as being as clean and pure as freshly-laundered, lily-white hankies,

whereas in the trashy, 1950s gangster novels of Hank Janson, the principal female characters

(molls) were painted as being more irredeemably stained and sullied than a jobbing printer's

apron - but here I'm digressing) a teleprinter alarm bell sounded to herald the arrival of a

high priority message.

Lady Luck could not have smiled more kindly, for the incoming cypher message was

designated 'operational immediate' and, best of all, was a full 900 words in length, which

meant five pages of letter groups with each group comprising of five randomly arranged, coded

letters. I deliberately waited for the first two pages of the message to emerge from the

printer before going to rouse Flt. Lt. Martinet from his slumbers in the officers' rest room,

calculating that the remaining three pages would have arrived by the time he was ready to

receive it.

He looked so peaceful in repose on the camp bed with the blanket tucked under his chin,

it seemed a crime to disturb him yet I delayed for not a moment and shook his shoulder gently

until he came awake and focused his bleary gaze on my face.

Blinking away sleep he croaked, "What is it?" I kept a noncommittal evenness in my voice

as I gave him the news, "There's an Operational Immediate signal for your attention, sir."

"Very good," he replied, before raising himself up on an elbow and clearing his throat. "Is it

encrypted," he enquired. "Yes, it is indeed sir."

I was on my way through the door before he chose to ask how long the message was. For

the first time during my period of service in Germany I experienced a delicious sense of what

I now know to be schadenfreude, as I added smoothly, "Five pages long, sir - 900 words in

total."

When he entered signals traffic a few minutes later his brow was clearly furrowed. I

came to attention and handed him the neatly separated five pages which I had paper-clipped

together, before making a deliberate show of busying myself with various administrative tasks.

Without saying a word he unlocked the cypher room door, entered, slid the door back again

and locked it. Next I heard him opening the heavy safe to withdraw the daily code book so that

he could enter the necessary settings into the Typex machine.

Some minutes later, having set up the machine and typed in the preliminary short piece

of code to verify the settings, he commenced typing the jumbled groups of letter code. Now,

when using the Typex, if one made a keystroke error it was immediately necessary to type in

either the letter Q or letter X. If this was done the machine would happily continue, but if

not it would break down and need a complete reset and the whole process would have to begin

again from the start.

This was a task requiring the skills of a polished, long-practiced touch-typist, not the

ham-fisted, clumsy, single digit keyboard prodding of a complete novice such as Flt. Lt.

Martinet. Three painfully slow attempts by him broke down well before the end of the first

line of letter groups - I didn't need to count them yet I knew exactly how many groups he had

typed before each separate failure occurred. Eventually, following the third breakdown, I

heard him sigh heavily, push back his chair and come to the separating door. I steadied myself

in anticipation of his next move.

When he stepped back into signals traffic I again came to attention facing him. "At

ease," he said somewhat awkwardly, "Now, what's your name, airman? I told him. "Yes," he said,

looking around the room but never directly into my gaze. "Well, er, Davis, I had a chat with

Squadron Leader (he mentioned a name) the other day who, er" - and here his voice took on a

pained tautness - almost as though he was about to draw one of his own teeth with a pair of

pliers - "who, er, suggested that if I got into trouble with this cypher thingy, that, er,

I could call upon one of you chaps for assistance."

I let the statement hang in the air for a moment or two. "That's something I can't

confirm sir, and I don't think it's fair that Squadron Leader (I repeated the name given)

should have mentioned such a thing because, as you must know, sir, we are not on the list of

permitted personnel for cypher duties, and the penalty - were we to be found in that section

- would be very severe."

"Yes, I see," he replied, "and I fully understand that, but are you telling me that you

have never given help to any other duty cypher officer?"

Determined not to make this easy for him I stiffened my resolve, "Yes, sir, that is what

I am obliged to say, otherwise my position is compromised."

At this point he must have realised he was backing me into a corner, and for the first

time stopped giving me the impression that he was dealing with an insufferable, young Bolshie

upstart (which, undoubtedly, he was) but relaxed his rigid posture and looked me directly in

the eye. "Look," he said eventually, in a much less authoritative and confrontational manner,

"there's clearly something else at work here that's causing your reluctance to assist me, and

it would be most helpful if you will tell me what it is?"

"Very well, sir," - and here I chose my words with particular care - "if you want me to

speak freely I will tell you: This is all very much about mutual trust and confidence."

"Hmmm," he mused, "trust and confidence, eh?. . . . Yes, I see. Well, on the issue of

trust, I can give you my solemn word that I will make no mention of your ever being in the

cypher office and, indeed, if that ever became known to higher authority, I too would suffer

the consequences."

"Oh, yes," I thought bleakly, "and while you are reeling from the effects of a minor

admonishment, I'll be getting marched in double-quick time through the gates of Bielefeld

M.C.C."

[Military Corrective Centre: An armed services form of prison, and certainly no Billy Butlins'

camp. This place was staffed not with jolly, smiling Red-Coats but hard-faced, and equally

hard-natured, army Red Caps, whose job it was to direct and control the unit's detainees'

daily programme of correction, all carried out with blisteringly high-speed movements.

Certainly not a place for the faint-hearted - and rather like Ratzeputz, - a highly-potent,

German alcoholic drink brewed in Celle, rumoured to cause drinkers' lederhosen to spontaneously

combust - best avoided if at all possible.]

- which was where, at that period, the British Army in Germany - and here I'm searching

desperately for a euphemism - 'straightened out' any warped, twisted, or wayward,

non-commissioned service miscreant.

However, he now had the bit between his teeth and had sighted the finish line: "All

right", he said in an emollient manner, "will you accept my suggestion that - with your help

and cooperation - we firstly expedite this urgent message and resolve any other related

matters later?"

That was it. He was clearly seeking a compromise, and it would have been silly for me to

persist because, as he then rightly pointed out, the message might well have a direct bearing

on every man in the bunker and beyond. And so it was time to haul down the Jolly Roger and do

my rightful duty for Queen and Country once more. Within minutes he had re-set the Typex and

I was applying my best efforts to the keyboard; the decoded printed message tape came

sprinting from the machine at a rate of knots that seemed to take him quite by surprise. All

he needed to do was glue the gummed tape in appropriately-sized lengths to the sheets of a

message pad. In less than twenty-five minutes, nine-hundred groups of jumbled letters had

been duly processed and the job was complete. His relief was palpable.

"Good, very good," he said, as he sorted and logged the finished result. "Well done.

Now, I will see to this, and return later."

Within the hour he came back, pulled up a chair, and gave me permission to be frank

and honest, and so I bit the bullet and did my polite best to let him know how resentful

we felt about his constant criticism of the signals' staff, all of whom, I emphasised,

customarily enjoyed the full trust and confidence of the unit's other cypher officers.

When I finished talking he said little other than that he appreciated my honesty.

He announced he would take away what I'd said and give it further thought. Before leaving,

he asked me not to mention to anyone what had passed between us, and I gave him that

assurance, and so at the morning shift handover I had to sidestep Tony Willis's gently

probing enquiries in relation to the most recent entry in the cypher log.

Belief Encounter

When I first began my service life I had the youthful notion that British officers were

a special breed. As an impressionable schoolboy I'd read Capt. W.E. Johns' "Biggles" books,

and comics such as The Wizard, The Hotspur and The Rover with their serial tales of manly

wartime British heroes; watched a myriad number of war films with actors such as, David

Niven, Jack Hawkins, Richard Todd, Trevor Howard, Kenneth Moore, et.al, portraying

stiff-upper-lipped, heroic figures, and so had the naive belief that, without exception,

our officers were honourable men beyond reproach.

However, a few short months in the ranks as an RAF Boy Entrant soon disabused me

of this idealistic fiction as, one fine autumnal afternoon, I was summoned to the

office of the Senior Education Officer for what I was informed was to be a 'career

improvement' interview.

Shortly after the commencement of the 'interview' I found myself being hotly pursued

around the office as a lusty, white-haired Wing Commander sought to educate me in a

manner that went far beyond any acceptable curricular boundaries.

Fortunately I had been forewarned, and having no intention of offering myself up as a

meek and submissive subject I adopted an 'Artful Dodger' routine: bobbing, weaving and

sidestepping his eager clutches until, after what seemed an age but was probably only a

couple of minutes, he realised I was not of his persuasion, and, as it happened - because

he had only one lung from which to draw breath - had simply run out of steam.

Relinquishing the chase, he leaned heavily against his desk, mouth wide open, gasping

for relief - in the manner of some old, unsuccessful and unrewarded circus sea-lion who

has wearied of performing - until he recovered sufficiently to dismiss me with a soundless,

flapping of a hand.

Curiously I felt no anger towards him, simply a mild feeling of outrage, though I do

clearly remember some time later experiencing a sudden flush of relief at my having

survived the encounter wholly unimproved. But though he may have been the first to sully

my rose-tinted view of the commissioned classes he wasn't to be the last.

At Celle, the Flight Lieutenant in charge of P.S.I. funds,

[P.S.I. Personnel Service Institute - a body set up to fund welfare and amenities for all

personnel from airman to corporal. P.S.I. shops sold all manner of goods: clocks, cameras,

etc., the profits from these going into P.S.I. funds.]

together with his wife - who, conveniently, was manageress of the P.S.I. shop - treated

the funds and shop proceeds as their personal piggy-bank. For quite some while they enjoyed

a fine old lifestyle until, inevitably, they reached a point where their submitted accounts

were found to be simply unaccountable, and shortly thereafter a couple of representatives

from the S.I.B. branch of the RAF Police paid them an early morning call.

And at Sundern, the Station Catering Officer, together with the active co-operation of

the Airmen's Mess Warrant Officer, ran a 'nice little earner' whereby official supplies for

the mess were redirected - through an equally corrupt local German supplier - in exchange

for markedly inferior victuals along with a cash sweetener of Deutschmarks. This went on

for months until the arrival of a new, keenly observant, and happily incorruptible sergeant

cook, who quickly brought their money-spinning activities to the attention of senior

authority, and who subsequently earned the unswerving gratitude of every airman on the unit.

But if now I have created the impression that our commissioned ranks were awash with

paedophiles, embezzlers and racketeers - whose initial letters might suggest the 'Per'

bit of the Ardua Ad Astra motto of the Royal Air Force is an unsavoury acronym - I must

immediately declare this to be completely false as, thankfully - other than for a certain

pompous percentage infected with an insufferable air of disdainful superiority - the clear

majority of our officers were commendably decent blokes who generally did their utmost to

keep the old flag flying, and who could be relied upon to uphold the best traditions of the

service.

However, I feel I ought to mention that, on occasion, I did encounter some rather

unpleasant exceptions to the rule, happily very small in number, who were, in my humble

opinion, rather less than worthy holders of the Queen's Commission, and among whom were

a couple of characters I would have been extremely reluctant to follow across the street.

But in happy contrast I also had the good fortune to run into a few genuinely

inspirational types whom I would willingly have accompanied to the ends of the earth.

But here my butterfly mind has been fluttering wildly away from the main thread of

these cobwebbed recollections, so let us now return to the Brockzetel bunker.

From fear to fraternity

On my late afternoon return journey to the radar site I was contemplating how best I

might cope with further, more searching questions from Willis, but I needn't have concerned

myself because it was a relaxed, cheerful boss who greeted me. Willis had been visited

that very morning by Flt Lt Martinet whom, it transpired, had delayed his return to Jever

in order to engage him in conversation, ostensibly to discuss some minor point of technical

detail in relation to cyphers, but who had then shifted verbal tack to where he spoke of

establishing a better understanding between himself and the signals' office staff.

Willis was never going to divulge the essential details of their confidential exchange.

But from the snippets he did reveal, it appeared the flight lieutenant might have undergone

something of an epiphany because - to his surprise- Willis had been complimented for the

'thoroughness and clarity' of his cypher training course.

When, a couple of nights later, it was again Flt Lt Martinet's turn to be duty cypher

officer. I took pains to ensure that my battledress jacket remained buttoned and my tie in

place and properly adjusted as I was determined not be caught 'improperly dressed', for I

had the uneasy feeling he just might be the type to harbour a grudge.

At some time after midnight the outer office door slid aside and he breezed in. I

immediately stopped what I was doing and raised myself to attention. All was tidied and

correctly in its place. As the Reverend William Archibald Spooner might have said, - that

is, had he been familiar with modern clichès - "I had all my little rooks in a

dough.".

As it happened, the Flight Lieutenant was in a surprisingly mellow mood. His customary

snap, crackle and popping rhetoric was noticeable only by its absence, replaced now with

calm and measured tones as firstly he told me to continue what I was doing before enquiring

if there was anything in the cypher 'in- tray' requiring his attention.

When I told him, "Nothing as yet, sir,", I fully expected him to turn on his heel and

depart, but instead he arranged himself comfortably in the armchair to watch in silence as

I waded back into the streams of signals traffic still swilling from the printers.

As the message flow eased I thought he might have seen enough but he stayed seated,

and when I, in turn, was also able to sit down he then began to ask a series of questions:

Where had I trained; was I a national serviceman or a regular airman; how long had I been in

the air force, etc., etc?

Still wary of him, I answered in the very briefest terms and after a while the

questions ended. Then to my astonishment he suddenly fished in a pocket and produced

a cutting from the Sunday Express which he invited me to read. It was by the paper's

gardening correspondent who was promoting the benefits of garden composting and how all

manner of plants could benefit from a generous application of well-rotted compost. "What do

you think about that?" the flight lieutenant asked.

I had to admit that my experience of gardening was extremely limited. "Limited to

what?" he enquired. So I told him the only thing I'd ever grown were garden peas that, as a

very young boy, I'd planted in the cracks between the paving flags in the backyard of our

terraced house in Lancashire and which, as they grew, I'd supported with a few twiglets. And

when he then asked if I'd had a crop, I had to confess the resulting yield had been somewhat

sparse; the few peas I was able to shell were pitifully small, pallid as little moons, and

completely flavourless.

His response was to chuckle before getting me to agree that if I'd fed the plants I

might have had some return for my efforts. However, though he laughed at the story of my

youthful gardening failure, it was evident that he was not laughing at me so much as

laughing with me, and about that point I began to feel less hostile towards him.

Thereafter, whenever it occurred that he and I were on night duty he began to drop in

for a chat, initially just for a brief visit, but as time went by the visits became longer

and could last for anything up to an hour. He also adopted the custom, of the other cypher

officers, of bringing two cups of coffee for us whenever, in the small hours, there was a

cypher needing to be decoded.

Our night time conversations ranged far and wide over any number and variety of topics,

but never included matters relating to RAF service, and nor did he ever refer back to our

initial exchange of words in the signals office. Once he borrowed a Louis Lamour western

novel from our office 'library' but within twenty minutes brought it back saying that he'd

managed to read half a dozen pages but that was as much as he could manage. In return he

lent me a couple of the early volumes of Henry Williamson's 'Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight',

for which I still remain grateful to him. (My own father had, at the age of 16, joined

the East Lancashire Regiment and served for three and a half years as a Lewis gunner in the

trenches of World War 1. He never spoke much about the war and it was only when I read

Williamson's barely-disguised autobiographical novels with their terrifyingly graphic detail

of the horrors of Flanders' fields, that I gained some small understanding of what my father

and his comrades had endured).

Never did I come to regard the flight lieutenant as a friend and, indeed, considering

the huge gulf that existed between us - he a middle-aged, ex-WWII navigator whose rows of

tunic ribbons were mute witness to his having flown through flak and enemy fighters, and

who somehow, with luck and a fair wind beneath his wings, had come through in one piece;

and myself: a barely-out-of-his-'teens, junior-ranking airman who had never had to confront

anything more challenging than his own woeful fear of the dark - this was more than just

improbable. No, any kind of friendship was simply out of the question, and yet - for

reasons I've never been able to fathom - we became comfortable and relaxed in each other's

company.

My office colleagues had suspicions that Flt. Lt. Martinet and I had some kind of

understanding because if I was out of the office when he popped in at night for a chat he

would ask when I was next on duty, but I never told anyone about our night duty

conversations as there was a real chance that some of my friends might come to regard me as

a 'creep', and consequently lose trust in me.

Gardening, it transpired, was the flight lieutenant's hobby, and once he revealed it

was his intention, when leaving the air force, to live on the west coast of Scotland there to

establish a rose garden and, hopefully, develop an entirely new variety of rose which he

intended to name in honour of his wife. He was raised in the western isles but saw Ayrshire

as being the county where he hoped finally to settle.

What impelled him to be the stern disciplinarian he could be is something he kept to

himself, but gradually over time I deduced that his upbringing had indelibly shaped and

defined him. He was s steadfast son of the Kirk whose moral compass needle had long been

set in unwavering alignment with the iron-clad, righteous certainties of his Calvinist

origins. Yet I also discovered him to be a man of integrity, humanity and decency who, when

at ease, revealed a pleasant and gentle nature. In addition to respecting him I found to my

surprise that I enjoyed his visits, and also came to realise that I liked him a great deal.

I have always hoped that he achieved his retirement dreams.

Subterranean site-geist

Some time before my arrival at Brockzetel, a few airmen of the new German Air Force

began training in the operations room. Initially, it was just a couple of handfuls of

officers and NCO's, but as the winter of 1958/9 retreated, what had been a mere trickle of

newcomers turned into a spring melt-water rush, and before long there was an almost equal

balance of RAF and GAF personnel.

Just as 101 S.U. personnel were shuttled between the bunker and Jever, the German

airmen were transported to and from their quarters at the former RAF station at Oldenburg

- which had been handed back to the German Air Force by the RAF in late 1957, about

eighteen months after the reformed GAF came into being.

Their officers and NCO's were mostly ex-Luftwaffe personnel, but if it felt somewhat

strange to be in close everyday contact with those who, until relatively recently, had been

sworn enemies, other than for the odd grumble and snort there was never any real

manifestation of ill-will from either side that I ever witnessed.

Officers sporting British wartime medal ribbons and those wearing former Luftwaffe

decorations appeared completely at ease in each other's company. This also applied with

other ranks, and when we began sharing the bunker's canteen and rest room facilities there

was a mutually friendly atmosphere. However, we did insist the Germans comply with our

habit of forming a polite and orderly queue for refreshments, etc., which, after some

initial resistance and confusion on their part at being obliged to fall in with this quaint,

old British custom - necessitating the occasional issue of a terse - but friendly spirited

- instruction, ("Oi, Hermann, get to the back!") - they happily conformed.

It wasn't long before both sets of blue uniforms mingled harmoniously in the rest room

swapping English and German cigarettes, although Players and Senior Service smokes were

universally preferred to the infinitely more pungent German brands with names such as H.B.,

Roxy, etc.

(Perhaps it's unfair of me to say that German cigarette brands were less than pleasant

to the senses but try, if you will, to imagine the scent of new-mown hay just after it has

passed through a camel, to understand why Brits and Germans alike opted for the superior

refinements of British tobacco.)

[Not to be confused with the popular American cigarette brand, Camel - which, incidentally,

was my favourite choice of 'weed' during a month-long detachment in January of 1961, to

RAF Muharraq, Bahrain. (Comedian Barry Cryer likes to relate that an American 'Camel'

cigarette advertising billboard of 1950s vintage, displayed a beautiful young woman enjoying

a smoke, with an accompanying caption which blithely announced, "I've tried the rest, but it

takes a camel to satisfy me.")]

At lunchtime in the above-ground mess, the Germans were allocated a separate servery and

dining area - their food being transported in insulated containers from their base at

Oldenburg just as ours came from the messes at Jever. (Officers had a separate dining

section). Ordinarily German and British other ranks didn't share mess tables but, because

of the limited size of the canteen, we were in close proximity and so each group was aware

of what the other was eating.

Their main courses appeared far more appetising than our own, but equally they were not

averse to casting an appreciative eye in the direction of what we enjoyed for pudding, and

especially on Thursday's when we were served a sweet pancake dotted with sultanas,

accompanied with a heavy dollop of custard. One day I did my bit to improve Anglo-German

relations when invited by a GAF airmen to exchange my pancake and custard for his main

course of wiener-schnitzel and brat-kartoffeln, to which I agreed in a flash - and this

swap became our habit whenever we met at Thursday lunchtime.

This wasn't first time I'd served at a 2nd TAF unit being readied for transfer. In

November of 1957, we'd handed back RAF Celle to the German Air Force (just a month after

Oldenburg was returned to them), and I was then moved to HQ 2 Group based at RAF Sundern (a

non-flying unit) near Gutersloh.

In my final weeks at Celle, I experienced the surprising novelty of being saluted by

junior members of the newly-arrived German air force. We later found that it was their duty

to salute any rank senior to their own, and though this caused much amusement in our ranks

it was nonetheless a slightly disconcerting experience.

Brockzetel's signals/cypher office didn't participate in training German airmen, and

remained the exclusive preserve of RAF personnel. The GAF trainees were concentrated mainly

in the large operations room on the lower floor, learning aircraft movement and plotting.

Judging by the increasing numbers of German personnel it was clear the handover of

Brockzetel was fairly imminent, and, indeed, this happened within a year or so - about the

same time Jever was also returned. To the best of my knowledge, and certainly for the five

months or so of 1959 I remained at the bunker, none of the technical sections were involved

in training GAF airmen, including the near-distant Transmitter and Receiver out-stations.

Apparently their technical system training didn't commence until about 1960, as recently

confirmed by my long-standing 101 SU chum, Phil Riggott, then a Ground Wireless mechanic.

Feature of the black lagoon?

Mention of Phil reminds me of the night I acted as his 'safety man' at the transmitter

block - located a couple of kilometres distant from the bunker. He says I volunteered for

the job, which surprises me because it was very rare for me to volunteer for anything, but

I suppose the chance of a night away from the hectic demands of the Signals Traffic office

had to be seen as a bonus.

Exactly what duty of care I was expected to perform was never clearly defined to me, but

I was not without a measure of youthful initiative, and remained alert and ready to cope with

any emergency; say, for instance, had Phil been working on a transmitter and been subjected to

a high-voltage charge, I would have leapt into action to find an non-conducting object -

most probably a wooden broom - with which to safely drag his charred and smouldering carcass

away from the point of electrical contact before making a telephone report of the incident.

Happily, Phil - like myself, a regular airman - had an ample measure of technical

ability coupled with a fair amount of experience and sufficient well-sharpened instincts

(well, he is from Sheffield) to ensure he stayed well clear of a lethal surge of juice and

so the night passed without incident. What also was a bonus was the fact that we were able

to enjoy several hours of sleep in the building's rest-room - never an option in the

Signals Traffic office where the norm was the occasional twenty minute cat-nap in the

armchair.

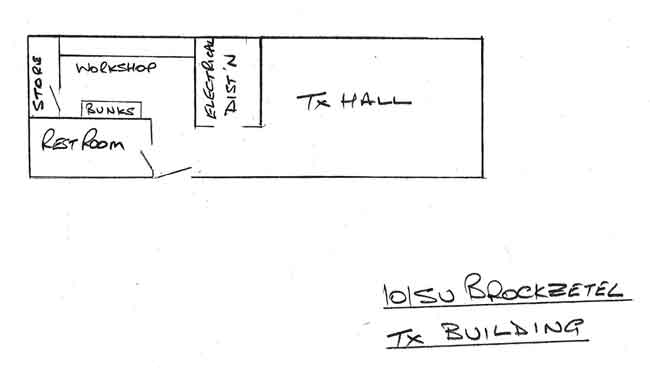

Phil has provided a rough sketch of the internal plan of the Transmitter building.

Exactly where the place was located I cannot remember, (Unsurprisingly, Phil and I failed

find any trace of it some forty years later in 1998, when we revisited the area). My only

recollection is that it was a bleakly unremarkable, single-storey, brick building with a

capacious hall in which stood three well-ordered ranks of UHF and VHF transmitter cabinets

emitting a soft menacing hum, from within which, when the main lights were off, a host of

thermionic valves glowed like busy fireflies. The building stood somewhere within the vast

peat bog which was a feature of the area, and though on our return some four decades later we

tried hard to locate it, we failed, and thus for all we knew the old place might possibly,

over time, have been sucked inexorably down into the glutinous, primordial soup of the

quagmire below.

[Since reading a draft of this piece, Phil Riggott called to say the 101 S.U. transmitter

building has now 'resurfaced' on Google Earth. Had it just been bog-snorkelling, I ask?]

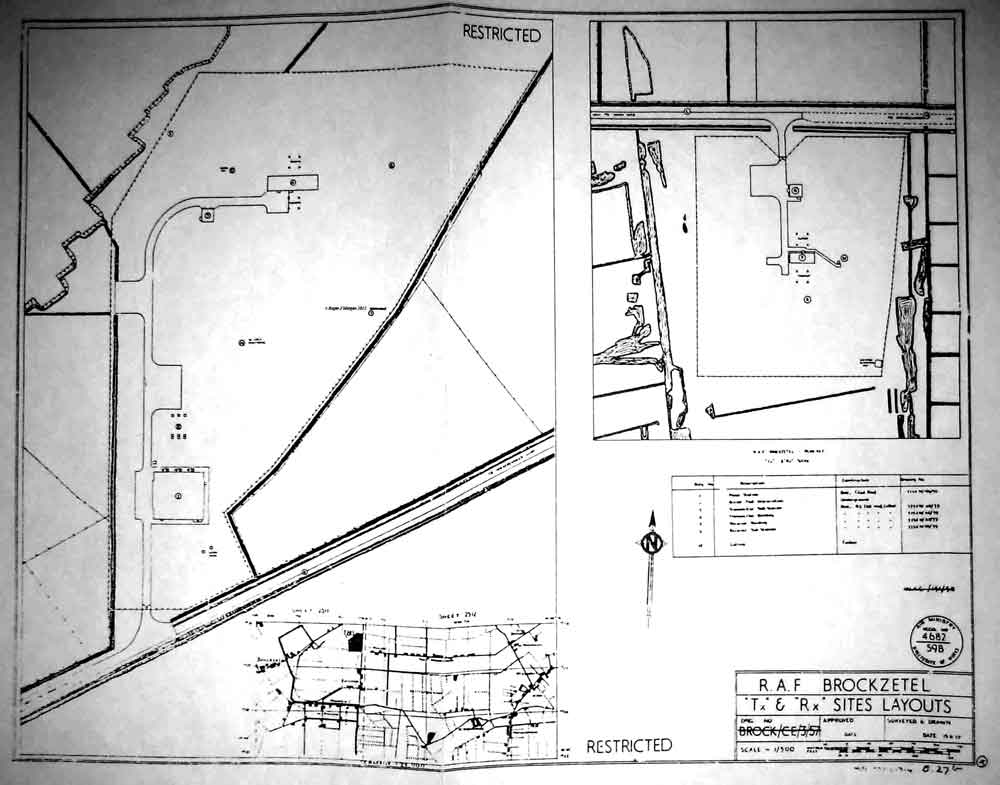

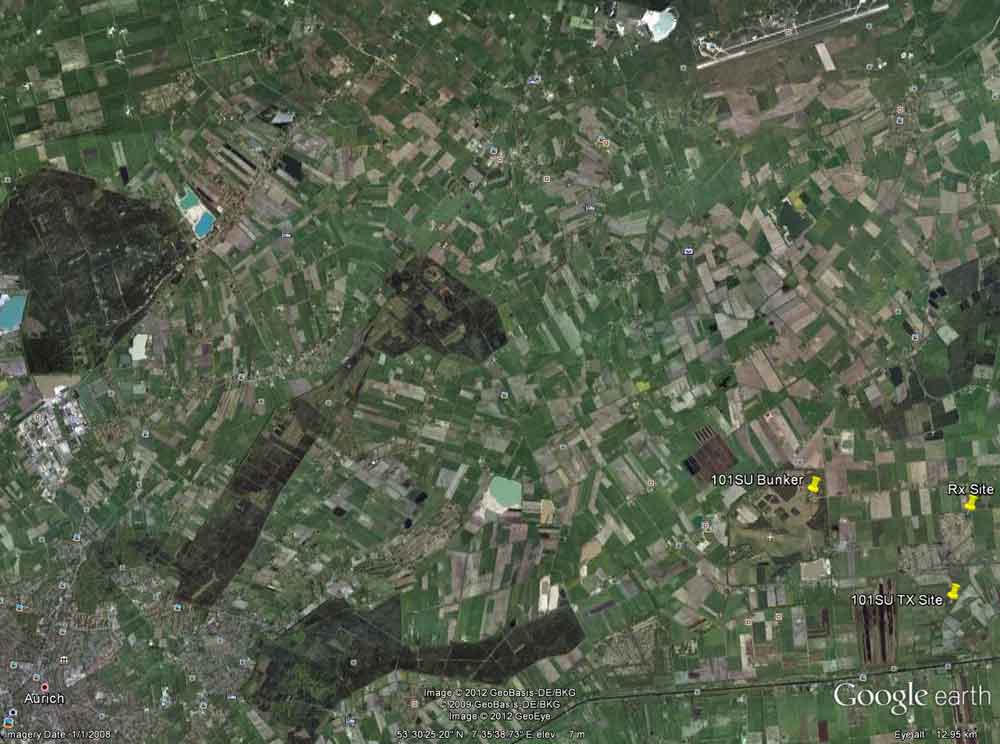

Detailed plans of main 101 SU sites.

Google Earth shots of locations today.

Google Earth shots of sites location in relation to the town of Aurich.

The High and the Mighty less so.

On entering the bunker by the stairwell and walking the highly-polished seventy-five

or so yards before passing a heavy, dome-shaped reinforced-steel blast door which brought

you to what I always termed, 'the inner sanctum'; one final turn of the corridor and a few

strides more brought you to a pair of swing doors through which was the operational heart of

the bunker. Adjacent to these doors was an alcove, (see on the left in the above plan), in

which stood a small, elegant mahogany side table on which lay a dark green leather-bound

visitors book. Above the desk, illuminated by a brass picture lamp, was a lovely picture of

the young Queen Elizabeth II - and I can't now recollect whether this was a Norman

Parkinson photograph or a copy of the portrait, painted during the mid-1950s, by Italian

artist, Pietro Annigoni, but I do recall that it was a striking image.

Occasionally I would scan the entries in the book to see if there were any names I

recognised. Most of our visitors were high-ranking officers from NATO forces, but

politicians sometimes came, most probably to check that we were providing value for money

(the bunker's construction and maintenance costs must have been huge). They were usually

government ministers accompanied by civil service mandarins from the War Office department.

A few of the political figures were vaguely familiar to me, but in honesty, most of them I'd

never heard of. They arrived and were probably briefed on the technical installations and

workings of the bunker before visiting the Senior Controllers' office to look down on the

virtually silent theatre of movement on the spacious operations room floor below, where the

only sounds came from the metallic exchanging of wall-mounted information boards, (rather

like racecourse tote betting boards) constantly updated by unseen operators working behind

the racks, whilst at the large central plotting table, a ring of airmen plotters were busy

pushing aircraft plots around the sectors of the mapped table, (something loosely akin to

the old game of battleships) all being directed, through headsets, by the sector controller.

One name I never uncovered among the multitude of entries in the book was that of

U.S. Air Force General Lauris Norstad, who at that time, was NATO Commander-in-Chief. A

couple of years ago, when looking at an official photograph of Norstad, I realised his

handsome countenance bore a more than passing resemblance to that of Hollywood screen actor,

Sterling Hayden.

(As you may recall, Hayden's most memorable movie role was as the mentally-deranged

U.S. Air Force General Jack D. Ripper in Stanley Kubrick's 1960's comedy-drama film,

"Dr Strangelove - or how I learned to love the bomb". Fortunately, for the sake of the

future of mankind, any other similarities between the real and the cinematic General ended

right there, and happily and fortuitously, throughout his tenure of office, Norstad's

mental marbles remained in well-balanced, rational orbit. Unlike Hayden's Ripper character,

he was never prompted by voices in his head to issue orders for a pre-emptive nuclear strike

against Russia. But here's a cheery little thought, if he had done so then it's just

possible at some point within the ensuing catastrophic maelstrom, the men of 101 Signals

Unit might have found their bunker to be little more than the world's most expensive

pressure cooker.)

The Wing-Commander. C.O. at Brockzetel often ran his eye over the latest entries in

the visitors' book. To his surprise and chagrin one morning he found a most unusual entry:

"L.A.C. Joe Bloggs - On Watch - 22.55."

As Leading Aircraftsman Bloggs hadn't bothered to disguise his real identity (which

I can't now remember) he was soon revealed as one of the units' telephonists. By chance,

he was the LAC who had been with me on the 11pm changeover shift the previous night, and

whose sole topic of conversation on the journey to the site was about his imminent 'demob'.

He repeatedly bragged that his 'chuff chart' - an alternative name for 'Demob chart' -

was almost complete, and that as a result we were all 'gripped' - (which meant - in

airmen's slang - that he held a clear advantage over the rest of us).

Joe was within a couple of days of finishing his two years of national service and

looking forward with relish to his return to 'civvy street'. As was the case with quite a

few national servicemen on the brink of release, he was floating in a mental transport-of-

delight - a condition we used to refer to as being 'Demob Happy' - a peculiar state of

mind which, in a few rare cases, could result in a state of euphoric bliss where sound

judgment and commonsense are temporarily suspended - but if Joe had thought his

'signing-on' in the book would not be uncovered until after his departure for the U.K.,

he was shortly to discover that he had miscalculated.

And so, within a few short hours of his leaving Brockzetel for what should have been

his last trip, Joe found himself heading back in the opposite direction, this time escorted

by a couple of S.P's, whose orders were to deliver him without delay for an appointment in

the C.O's office. Those of us who heard about it, reckoned that Joe's national service was

about to be extended by a period of at least 14 days of 'jankers',

[Jankers: Punishment for a minor breach of the rules where an offender is confined to camp

and required to parade four times a day in full kit at the station guardroom. He was also

given 'fatigues' each evening during his punishment, usually dirty, boring and menial tasks

such as cleaning cooking trays in the airmens' mess. Offenders were known colloquially as

'janker wallahs'.]

but to our complete astonishment, a few hours later he showed up again in a state of mild

shock grinning sheepishly like a man whose neck has just been spared a visit from the axe.

Having been invited by the C.O. to explain himself, Joe had shrugged and told him that

he hadn't much to say in answer other than he had simply yielded to a reckless and silly

impulse to add his name to the list in the book before saying his final 'goodbye' to 101

Signals Unit and heading for Blighty. And having made this confession he'd probably

steeled himself in anticipation of the inevitable swish of the blade - but it never came.

Instead, in a wholly unexpected and rare act of leniency, the C.O. merely handed him a

bottle of ink-eradicator and ordered him to carefully erase his entry in the book, after

which he would be free to leave.

A few weeks after Joe's departure I too was on my way back to the U.K., having been

posted to Southern Region Air Traffic Communications Centre at RAF Uxbridge, and though I

would have much rather been posted to a flying unit, the prospect of being just a tube

journey from the centre of London was quite a thrill.

Exactly what happened to the Brockzetel visitors' book, I have no idea. Occasionally

I look on Ebay to see it's up for auction but as yet I haven't seen it listed. Should any

of the Jever Steam Laundry members know of its whereabouts could I mention that if

they're tempted to put it up for sale then - in order to add it to my little collection

of RAF memorabilia - I'm willing to go all the way up to a tenner and, for good measure,

throw in a couple of old Baffs as a sweetener.

. . . . . . .

* May I offer grateful thanks to Phil Riggott & Maurice Gavan for their input, advice

and support to me during the writing of this piece.

|