|

Air Vice-Marshal Sir John de M Severne KCVO OBE AFC DL Flight Commander on 98 and later Captain of the Queen's Flight |

||

|

John joined No 98 Squadron on Venoms at RAF Fassberg in January 1954. By July 1954 he had been appointed a Flight Commander under "Boss" Sqn Ldr Smith-Carington. James Robinson, an airman from 118 Squadron serving at Fassberg at the time sent me the following two clippings from newspapers of the day:

Then in Flight this week 8-14 March 2005, on the "50 Years Ago" page, the following report. (Copy sent to John by Bunny Bramson):

John's comments on this Flight report were as follows: "The story is basically right, however I took off from Fassberg, not Wunstorf, I was at 10,000 ft not 8, I was overhead not 10 miles away and I certainly did not hack off the engine cowlings. The fire engine drew up alongside as I came to a halt and the firemen and I unscrewed the cowlings (albeit fairly quickly!) and I asked the foremen not to cover the engine in foam because I wanted to preserve as much of the evidence as possible, hence the use of CO2 or whatever it is. The engine was still smouldering. I was extremely lucky because several pilots had been killed after the elevator cables burned through. The thing that amazed me was how gentle the belly landing was. It was the same sensation as landing a helicopter with skids engine off. The reason was obviously that the lift degrades gradually and not at the moment of touchdown. But I did not expect it - I thought it would be a bumpy ride! I landed wheels up on the grass because I wanted to evacuate as quickly as possible as I did not know what was going on behind me." Unfortunately, all of the clippings were undated, so I rang John and he not only dated the event but even better sent me a copy of Chapter 6 of a book he is writing about his time in the RAF. He has kindly allowed me to reproduce the Chapter completely. He is writing the book for the benefit of his family and I recommended he published it for anyone to buy as it is also a fascinating record of everyday life in RAF Germany in those days which should be captured for future generations. The date of the fire and crash landing was 1st November, 1954. (Click here to see the story). Here is the full Chapter 6 of John's story: 6. Back to the front line Towards the end of my tour as a CFS instructor I applied to join No 2 Squadron in Germany equipped with Supermarine Swifts in the fighter reconnaissance role. It was commanded by Squadron Leader Bob Weighill who had been my squadron commander at Cranwell when I was instructing. He said he would be willing to apply for me, but pointed out that I should be due to become a flight commander, and that would not be possible on 2 Squadron because both positions were already filled. I therefore applied to join No 98 Squadron, then based at Fassberg and flying the De Havilland Venom Mk 1. The Squadron was commanded by Squadron Leader John Smith-Carington who had been with me on the same course at the Central Flying School five years earlier. He agreed to apply for me, but said I would have to wait my turn to become a flight commander because a post would not become available for a few months. I gladly accepted this situation and was duly posted to Fassberg in January 1954 after attending the Operational Conversion Unit on Vampires at Chivenor. Fassberg was a magnificent ex-Luftwaffe base that the allies never found until towards the end of the war. It is in a large forested area and was well camouflaged. It was about 80km south east of Hamburg and very close to the notorious concentration camp at Belsen. It was also quite close to the Iron Curtain and great care had to be taken not to accidentally fly into the Russian Zone because that tended to upset the Russians and invariably resulted in formal diplomatic complaints. There were two other Venom squadrons at Fassberg: Nos 14 and 118. Whilst each squadron had its own distinctive spirit, the morale of the station as a whole was exceptionally high and although we flew hard we also played hard! The Venom was a good aircraft and was pleasant to fly; it performed like a hotted up Vampire and in particular it had a good high altitude performance. Our role was DF/GA - Day Fighter and Ground Attack. In the ground attack role we liaised closely with the army and co-operated with them on frequent exercises. So that we understood each other as best as we could we used to invite army officers to spend a few days with us and to fly in the two seat Vampire which we used for training and the checking of our own pilots. In turn some of us volunteered to spend a few days with the army. I asked if I could spend a week with the Royal Welch Fusiliers who were based to the north of us at Luneburg. Their commanding officer said that he would be glad to have me, but they were very busy at the time training for the Korean war and that, if I wanted to come, I would have to do a job of work. Of course I agreed, but was rather surprised to find that I had been appointed as a platoon commander for a week! The troops accepted the situation in very good heart and I had excellent guidance and support from their platoon sergeant. On our last day, a Saturday, I was marching up and down with two other junior officers waiting to go on parade when one of them said: "How have you enjoyed your week with us?" I replied that I had enjoyed it immensely, but that I now knew that I could never make a soldier (I had always known that, but I didn't admit it!). "Why ever not?" one of them said, "you have done alright with us" to which I replied that, whilst I had enjoyed the week, I could never actually enjoy crawling around in freezing mud being shot at. To which I received the astonishing reply: "But surely you don't actually enjoy flying those things do you?" It hadn't occurred to them that pilots in the RAF thoroughly enjoy their flying. I think it would be very difficult to become a pilot if you were not enthusiastic about flying. Indeed I would go so far as to say that you can't do anything in life really well unless your heart is in it and you enjoy the work. Having said that, I was full of admiration for the qualities shown by the junior officers in the army towards their men. From day one they are taught to be good "officers", and as infantrymen they will be in charge of thirty or so men as soon as they join their regiment. They learn how to deal with some pretty tough characters and how to turn them in to good soldiers whilst at the same time being concerned about their welfare, whereas in the RAF our primary concern when we first graduate to a squadron is to be busy learning how to operate our aircraft, whilst the airmen who service our aircraft our commanded not by the pilots, but by their engineering officers. It is therefore quite possible for an RAF pilot not command airmen directly until he becomes quite senior, possibly not even until he becomes a group captain station commander. This might account for a remark made to me when I was on my first squadron. I was a newly commissioned pilot officer driving past Pocklington in Yorkshire when I stopped outside the Army base there to pick up an airman in uniform who was thumbing a lift to York. I was in civilian clothes and there was nothing to suggest I was in the RAF. I was intrigued to find out why an airman was working on an army base so we got into conversation. It seemed he was a signals specialist who was on a course with the army signalers so I asked him what he thought of the young army officers who were looking after him. He said he was full of admiration for the way they would come into their barrack huts and chat over any problems, helping wherever they could. "What do you think of the RAF officers then?" I asked, silently hoping to be flattered. That turned out to be a silly thing to have asked because he replied: "Between you and me sir they are a lot of spivs!" I hoped he was wrong, but I understood the point he was making and, as the years rolled by, I tried not to forget that lesson. Six months after joining 98 Squadron I became a flight commander. I tried hard to inject enthusiasm and fun into the training of the pilots, because, as I said earlier, I didn't believe they could do their job properly if they didn't enjoy it. This obviously paid off because one night in the bar, doubtless after quite a few jars of the excellent German beer, one of my officers came up to me and thanked me for giving him back his enthusiasm for flying. I was keen to fulfil my second ambition of owning a Mercedes. Unfortunately the sports cars I was interested in were extremely rare, but pre-war saloon cars were obtainable. I managed to buy a 1938 Mercedes 230 which had been a German Army staff car and which had survived the war. It was in remarkably good condition, apart from the fact that it seemed to consume more oil than petrol. It was built like a tank and had independent suspension on all four wheels. It cost me #85 and I was very proud of my new possession. After three months or so we were allocated a married quarter. My wife then flew out from UK with our two young daughters to join me and I met them at Hamburg with the car I had just bought, hoping fervently that it would not break down on the way to the airport. We were delighted with our ex-Luftwaffe officer's quarter; it was built with double glazing and central heating which was a good thing because the temperature would drop to around zero Fahrenheit in the winter. We take these things for granted now, but at that time double glazing was virtually unknown at home. I have to admit that times were hard then for the Germans, but British forces were very well looked after. As a flight lieutenant we were entitled to a full-time house keeper, a full-time living in nanny for the children (a very nice young German girl called Irma), a part-time gardener and also a part-time boiler man to stoke our central heating boiler twice daily. We had a petrol ration, but the petrol was cheap for the forces. With a young family at that time the domestic help was particularly appreciated. On the station we had a good riding stable with several horses and a full-time German groom. My wife and I spent may happy hours riding in the forest of Vrrel which bordered the airfield and it was not long before I was found out and made officer in charge of the stables, but this time it was doing something which I thoroughly enjoyed, and perhaps more importantly, it was something we could do together.

At about the same time as I was appointed a flight commander, Fassberg was tasked with carrying out trials and demonstrations of the use of napalm. I was one of two pilots selected for this interesting activity. Napalm is jellied petrol which was carried in fuel tanks slung beneath the wing (I think they were 100 gallon tanks) and which could be jettisoned. The effect viewed from the ground was dramatic and to some, quite frightening. We used a Vampire Mk5 and most of the trials and demonstrations were carried out on the range at Fassberg. The technique was to approach the target at 360 knots at 20 ft and this itself was quite exciting! There was no bomb sight of any kind and we dropped the "bomb" by eye by simply pulling the jettison lever. After a little practice we were able to achieve direct hits on most occasions. Most of our practices were carried out with water in the tanks, but even that was quite impressive. I remember one of those demonstrations very clearly: I flew from Fassberg to Tangmere and from there to take part in a "Fire Power Demonstration" on Salisbury Plain. These demonstrations were held regularly to show off the various military and air force weapons the UK On my return from Tangmere the day after the demonstration the weather over Germany was very poor. On starting my descent I was not sure where I was so I asked for a bearing to Fassberg. This is given by an operator on the ground who can tell the direction of the radio transmission from the aircraft. After a number of bearings had been transmitted I became suspicious because I felt certain I must have passed over the top of Fassberg and was therefore heading for the Russian Zone. After checking, the operator admitted he had been giving

me reciprocal bearings, in other words I

We enjoyed flying the Venom, but it did have its problems when it first came into service in 1953 and these are well documented in David Watkins' excellent book "Venom". He tells of how Sam D'Arcy of 14 Squadron ejected in March 1954 when a wing broke off as he was pulling out of a practice dive bombing attack on the near-by range near Fassberg. He was so low when he ejected that his parachute had only just deployed when he hit the ground. (Click to see press report). I met him in the bar very shortly after the incident and his face was cut and bruised because he did not have time to jettison the canopy before he ejected, so he ejected through it - hence the battering on his face. (Click to see). However his injuries were superficial and he was enjoying his well deserved drink! There had been several previous accidents when the wings failed and until the aircraft were modified they had red bands painted on the wings to remind pilots to limit the g forces. We also had a number of inexplicable fires in the air and several pilots had been killed when attempting forced landings because the fires had burnt through the flying control cables. Pilots were therefore given strict orders to eject if they had a fire and not to attempt a forced landing, even if the fire appeared to be out. Venoms of 98 Squadron photographed by one of our pilots, Brian Sharman In October 1954 one of the pilots on my flight, George Schofield, had been killed when he attempted to land after a fire. Four days later on the 1st November I was at the top of a loop at 10,000ft over Fassberg when I decided to hold the aircraft inverted for a few moments before rolling level. Whilst still inverted there was a bang, the fire warning light came on and the cockpit filled with smoke. After completing the fire drill, which obviously included shutting down the engine, I prepared myself for a forced landing on the airfield which I could see clearly beneath me. I knew I was under orders to eject, but I was very conscious of George's accident and I was overcome by a conviction that this had happened to me, his flight commander, so that the riddle of the fires could be solved. I decided to land wheels up on the grass by the side of the runway so that I would be able to get out of the aircraft quickly if needs be. We had all regularly practiced forced landings and, with height to spare and perfect weather, I had no difficulty in positioning my self to land alongside the runway in use. I had never landed wheels up before and I was surprised how gentle it was. The moment I came to a halt the fire engines were alongside and, since there was no obvious signs of the fire still burning, I prevented the fire crews from smothering the engine in foam in case this destroyed valuable evidence. The first thing I did when I got back to our hangar was to brief the other pilots in the crew room what had happened and to emphasise that under no circumstances were they to attempt to land after a fire - they must eject. Shortly after that the Wing Commander Flying entered the crew room and gave me a severe ticking off, and then added "but well done!" It appeared that he had also been airborne at the time and heard what was happening over the R/T. He knew he should have ordered me to eject, but I gather he sensed what I was trying to do and kept quiet. The Board of Inquiry thought the fact that the fire started whilst I was inverted might be significant so they rigged up a complete Venom fuel system upside down in a hangar and they did indeed solve the problem. I have to admit that for the first few sorties after that incident my eyes tended to concentrate on the fire warning light and it took me a month or so before I was able to relax in the cockpit. Venoms were not the only aircraft that tended to catch fire. The Americans were flying F84 Thunderjets in their zone to the south and the story was around that if these aircraft caught fire you had four seconds to eject before the whole lot exploded. One of the aircraft in a formation caught fire and one of the other pilots shouted on the R/T "Hank, you're on fire", whereupon four Hanks throughout the zone ejected! I don't know how true the story was, but it was often used as an example of why strict R/T discipline is essential. If the pilot's callsign had been used rather than his first name, three aircraft would have been saved. Shortly after my Venom fire I fell asleep at the wheel of our Mercedes one night returning from dinner with an old friend at the Officers' Club at Celle. The road went round a corner at Uelzen, but unfortunately I went straight on. Despite the fact that we broke a telephone pole in two, the damage to my tank-like Mercedes was not severe, but the damage to my wife was. This was before the advent of seat belts and she had been thrown forward, her face hitting a sharp knob which was used to open the windscreen. She cracked a collar bone, but much more seriously fractured her cheek bone in many places, the knob missing her eye by a fraction of an inch. If we had been wearing seat belts she would have been un-injured. On the other hand I have always felt that had the car been of a more modern flimsy construction, we might both have had serious injuries. In those days no countries had drink-and-drive laws and I realise I was probably over the present day limit. It is a sad fact that few of us serving in Germany at that time completed our tours without having some sort of road accident. In the spring of 1955 I was sent on the Day Fighter Leaders Course at West Raynham. This was an excellent two month course learning, as the name implies, how to be a fighter leader both in air defence and ground attack. Most significantly to me the course flew the new Hunters which had first come into service the year before. These were the Mk.1 Hunters which were a great advance over the Venom and whilst they were a delight to fly, were a bit limited on fuel. After 40 minutes at low level one was really starting to get worried! The course taught us how to operate the aircraft to its limit, so much so that on one sortie, one of the members on our course ran out of fuel whilst taxying back in.

I returned to 98 Squadron after the DFLS course, but by then the squadron had moved to Jever, not far from Wilhelmshaven, in the north of Germany and had re-equipped with the Hunter Mk 4. This was a very flat uninteresting area of Germany, not far from the North Sea. The air was often damp and many of the children including ours had ear problems. We sometimes took the children with Irma to the sea for the day on the north coast at Shillig, the nearest sandy beach. Irma had come with us from Fassberg and the first time she saw the sea she asked "what are those funny white things?" She had never before seen the sea, let alone white horses. Although the war had ended five years before there was very little socialising between us, yet on the whole our relationships with the German population were good. However, things appeared to be different in Holland, or so I discovered to my embarrassment. Sometimes we would treat ourselves to a day's shopping over the border in Holland, usually at Groningen, and on one occasion I stopped to fill up with petrol. I had not learnt to speak German properly, but I knew enough to be able to shop or ask the way. When I stopped at a garage to fill up, without thinking I spoke in German and said "zwanzig litre bitte". Whereupon an angry Dutch garage owner, recognising us as British, said in English "don't you use that language in my country." I realised then that there still was no love lost between the two nations. Brian Sharman photographs a happy flight commander

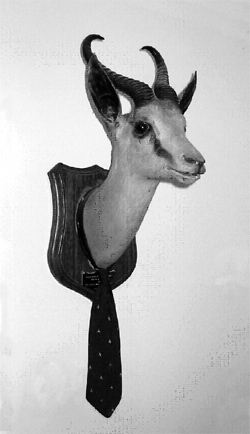

We had a station farm at Jever which provided us with fresh food and vegetables. We adopted as a mascot one of the pigs whom we named Elspeth. She was a great supporter of the squadron and would appear on major occasions. One of the other squadrons at Jever, 93, was operating the North American F86 Sabre Mk4. Ever anxious to get my hands on a new type I persuaded their squadron commander to let me fly one of his aircraft. My main impression of this excellent machine was the huge cockpit. British cockpits of fighter aircraft tended to be cosy with everything close at hand, but the Sabre's cockpit seemed massive compared to anything I had been used to before. [Click to see 93 Sqn F540 report of this event]. At that time the six monthly promotions used to be announced the day before they were to take effect on 1st January or 1st July each year. This usually meant a move to a new unit within two or three weeks of However, true to form I was posted within a fortnight to RAF Oldenburg, near Bremen, to command No 26 (Army Co-Operation) Squadron which had already re-equipped with the Mk4 Hunter. I arrived on the station on the evening of the 15th January and the following morning asked the way to our hangar. There was no one to meet me so I asked the way to the CO's office and started from there! My predecessor had already left and I therefore had no hand-over. Luckily I had two experienced flight commanders, one of whom, John Crowley, had been a test pilot developing the Hunter at Boscombe Down. I flew with the squadron for the first time that night, a sort of mirror image of my last flight as a flight commander, also at night. 26 Squadron was formed after a group of South African pilots, who had learned to fly in England before the outbreak of World War 1, formed a unit at Farnborough in November 1914 which then went off to serve in the campaign against the Germans in South West Africa. The origins of the squadron account for the squadron badge depicting a springbok and an Afrikaans motto: "N Wagter in die Lug" - watchers in the sky. In 1953 the South African Air Force presented the squadron with a fine springbok's head and this was mounted on the wall in the CO's office behind his chair. In the summer of 1956 we went on a three week camping holiday through Bavaria and Austria on our way to Venice. By the time we got to Vienna the temperature was 104° and already a 2 Ltr bottle of cider had exploded in the back of the car making a ghastly sticky mess. We had had enough by then and decided to stay put for a week or so in a delightful camping site in the Vienna Woods just outside the city before returning. This proved to be good decision and we came to love Vienna. We were particularly lucky to be able to see the wonderful Lipizzaner stallions of the Spanish Riding School performing in their beautiful baroque Riding Hall, led by Colonel Podhajsky who had revived the school after the war. Poetry, art and music in motion seems to sum up their superb performance. Married quarters were allocated on a points basis, points being awarded for seniority, length of time being married, number of children etc. and several of our young officers who had not yet gained enough points were not able to have their wives join them in Germany. Therefore, those of us lucky enough to have quarters, usually let these un-accompanied officers stay in our houses when we went on leave so that they could bring their wives out from UK for a holiday. We did just that on our camping holiday to Vienna. There must have been some misunderstanding about the date of our return because, when we arrived home after a 600 miles journey home travelling through Austria and Germany, we found that our guests were not expecting us to return until the next day. We could not possibly turn them out of the house that evening, so we happily set up our tent again, this time in our own garden! John Crowley's expertise came in very useful when we had some fairly serious problems with the Rolls Royce Avon engines of our Hunters. The engines tended to surge at high altitude when pulling high g forces which often resulted in a flame-out. Whilst it was easy to relight the engines, it would not exactly be helpful to experience an engine surge in combat. John assured us that the engines should be able to operate correctly at high altitude and we should persevere with Rolls Royce and Boscombe Down to solve the problem. We were loosing quite a bit of flying time with unserviceable aircraft because of these difficulties and my station commander (a group captain who will remain nameless!) called me to his office and said: "Unless you can achieve more flying hours like the other squadrons I will find another Geoff Wilkinson, the senior flight commander, formed and led a formation aerobatic team which became the representative team for the 2nd Tactical Air Force in Germany. I commissioned a young German artist, Bruno Albers, to paint a picture of the team and this I presented to the squadron. Bruno had never flown, yet I think he successfully caught the feeling of what it is like to wheel amongst the clouds. I well remember briefing the squadron the day the 1957 Duncan Sandys Defence White Paper was published. The government had said that manned aircraft would be replaced by un-manned aircraft and this, of course, had a disastrous effect on morale throughout the RAF. Initially it even effected recruiting because parents and head teachers saw no future for flying in the RAF. How wrong Duncan Sandys was is indicated by the fact that there is little sign, nearly 50 years later, of pilots becoming redundant, although the use of un-manned aircraft is certainly on the increase as proved by their involvement in several recent wars. The 26 squadron Formation Aerobatic Team

26 Squadron was disbanded at Oldenburg in September 1957, only to reform a year later at Gütersloh with Hunter Mk 6s and these it flew until disbanding yet again in December 1960. In 1962 it re-formed with the twin rotor Belvedere helicopter and saw sterling service in Aden during the Radfan Campaign for two and a half years before disbanding again. It finally reformed in 1969 at Wyton as a non-operational communications squadron, disbanding for good on 1st April 1976. Before disbanding the squadron tried to contact all those who had given silver and pictures etc. so that these items could be returned to the donors rather than have them put away and forgotten in some Maintenance Unit. The picture of the formation aerobatic team was therefore returned to me. I was worried about the future of the springbok head so I asked the CO what had happened to it, whereupon I was told that it had been badly damaged and they had thrown it away. I was not amused and asked if it could be recovered so that I could collect it. This I did and found that the whole of the front of the head had been broken off so I went to our sick quarters (now they call them Medical Centres!) and asked for some plaster of Paris and then repaired the head. I was pleased with my handwork and the scar can hardly be seen. The springbok now wears a squadron tie and is proudly displayed at home. The springbok's head in retirement DAILY TELEGRAPH OBITUARY dated 9th October 2015 Captain of the Queen's Flight who flew varied aircraft all over the world during the 1950s and 1960s.

Ever since he was a small boy building model aeroplanes, Severne had been passionate about flying. His career in the RAF ranged from post-war fighters and jet trainers to the Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft. He won the King's Cup Air Race in 1960 and became the British Air Racing Champion the same year, flying a Turbulent aircraft entered by the Duke of Edinburgh. In addition to the 32 service aircraft types, he flew 39 different civilian light aircraft. The son of a Royal Flying Corps observer and doctor, John de Milt Severne was born in London on August 15 1925 and educated at Marlborough, where he served in the Officer Training Corps and Home Guard. He was a light aircraft enthusiast from his first flight in a Gipsy Moth at the age of 10. He joined the RAF in April 1944 and completed his training as a pilot in October 1945. He first flew the Mosquito night fighter with 264 Squadron for two years, before leaving for the Central Flying School (CFS). He trained as a flying instructor and spent the next few years teaching student pilots before returning to CFS to train instructors. In 1952, while still serving at CFS, Severne was able to participate for the first time in the King's Cup Air Race, an annual event that had fascinated him from his school days. In January 1954, he joined No 98 Squadron, flying Venom day fighter/ground attack aircraft based in northern Germany close to the Iron Curtain. He was soon appointed a flight commander. On November 1 1954 he was carrying out a looping manoeuvre when the engine of his Venom caught fire. A few days earlier a colleague had suffered the same failure and had died when he tried to land the aircraft. Severne would have been justified in ejecting from his single-engine fighter but elected to crash land so that investigations into the incident could be carried out. He landed alongside the runway with the wheels retracted as the fire continued to burn, and managed to scramble clear. For his gallantry he was awarded the AFC. He converted to the Hunter fighter and in January 1956 took command of No 26 Squadron, also based in northern Germany. Following the 1957 Defence White Paper, which stated that air-defence missiles would replace manned fighters, Severne had the distasteful task of telling his men that their squadron was to be disbanded. After a year in the personnel department of the Air Ministry, Severne was appointed to be Equerry to the Duke of Edinburgh. Among other duties he was responsible for making all travel arrangements for the Duke and accompanying him on many trips. This allowed him to travel with the Queen's Flight and he took the opportunity to learn to fly helicopters. In 1959 Severne entered King's Cup Air Race flying a Turbulent painted in the Duke's colours. After a creditable performance, the aircraft was entered again the following year. A number of modifications were made, which resulted in Severne winning the coveted King's Cup while wearing his daughter's riding hat as a crash helmet. After two years, and promotion to wing commander, Severne was appointed LVO and returned to RAF service. After completing the RAF Staff College course, he flew Javelin and Lightning fighters during his appointment as wing commander flying at RAF Middleton St George (now Teesside Airport). With the closure of the RAF airfield, he became the chief instructor of the Lightning Operational Conversion Unit at Coltishall in Norfolk. Severne's next appointment was a very different affair. He left for Aden in January 1966 as the political situation in the Protectorate worsened. He was responsible for the operations of fighter and maritime reconnaissance aircraft, and helicopters working in co-operation with the Army. Hunter aircraft, which he flew on operations, were kept very busy patrolling the Yemen border and attacking dissidents. The Shackleton maritime patrol aircraft were heavily engaged in the Beira Patrol, the implementation of the Rhodesian oil embargo. As the dissident and terrorism activity increased, Severne was also heavily involved in the planning for the withdrawal from Aden of British forces scheduled for November 1967. On November 28 he was one of the last RAF officers to leave Aden. For his services he was appointed OBE. Severne's already varied flying career took another turn in January 1971 when he was appointed to command the RAF's largest maritime base at Kinloss in Scotland. His three squadrons of Nimrods patrolled the North Atlantic shadowing Soviet submarines and powerful surface fleets. He accumulated almost 500 hours flying time in two years and once commented: "Flying low over the sea at 200 ft, at night, in bad weather, 1,000 miles over the North Atlantic, concentrates the mind no end." He also flew the Shackleton in the airborne early warning role. During his command of Kinloss, the station was awarded the Wilkinson Sword of Peace for 1971, which he accepted from the Duke of Edinburgh. In 1972 he was appointed as an ADC to the Queen. After attending the Royal College of Defence Studies, Severne returned to the Central Flying School as Commandant. This provided him with a wide variety of flying opportunities with the RAF, including having the Red Arrows under his command. After leaving CFS in February 1976 Severne spent two years responsible for all flying training in the RAF before taking over as Commander, Southern Maritime Region, an appointment that also carried two senior NATO war appointments. He controlled all British and NATO maritime aircraft, when operating out of British bases, south of a line from southern Ireland to Greenland. He also controlled the Rescue Co-ordination Centre, which included air-sea rescue helicopters. His last flight in the RAF was piloting a Whirlwind helicopter during a training air-sea rescue sortie. He retired from the RAF in 1980. In 1982 he was recalled to be Captain of the Queen's Flight and a member of the Royal Household. Severne travelled worldwide with members of the Royal family. After seven years, he finally retired, at which point he was advanced to KCVO. His retirement to Somerset was almost as busy as his service life. He served as a Deputy Lieutenant of the county from 1991 to 2001 and was Honorary Air Commodore of No 3 Maritime Headquarters of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. He was president of the SW Region of the Royal Air Force Association and also president of the Queen's Flight Association and of the Central Flying School Association. A man of great charm, he was a keen photographer and took a close interest in local affairs. He was Chapel Warden at Ditcheat Church and raised £25,000 for the restoration of the church's Alhampton Chapel, a project completed in 2011. He wrote his autobiography Silvered Wings in 2007. He never lost his love of flying and a week before his 90th birthday, and 80 years after his first flight in a Gypsy Moth, he took the controls of a Tiger Moth. John Severne married Katharine Kemball in November 1951. She and their three daughters survive him. |

was going in the opposite direction to that intended. After landing we calculated that I must have been at least 20 miles into the Russian Zone and we therefore waited for the inevitable diplomatic complaint. It never arrived because we learnt later that the Russian radar was unserviceable on that day.

was going in the opposite direction to that intended. After landing we calculated that I must have been at least 20 miles into the Russian Zone and we therefore waited for the inevitable diplomatic complaint. It never arrived because we learnt later that the Russian radar was unserviceable on that day. squadron commander". Although I did not express it at the time I was furious at this comment because I knew the other squadrons were minimising the problem at that time by doing much of their training at low level, but I couldn't say that to the station commander. Engineers and test pilots visited us and eventually the problem was solved. This was effectively demonstrated by John Crowley leading all 14 of the squadron's aircraft in a formation flypast over the base. This happened during our camping holiday and was a very welcome surprise on my return, even if I had missed the fun myself.

squadron commander". Although I did not express it at the time I was furious at this comment because I knew the other squadrons were minimising the problem at that time by doing much of their training at low level, but I couldn't say that to the station commander. Engineers and test pilots visited us and eventually the problem was solved. This was effectively demonstrated by John Crowley leading all 14 of the squadron's aircraft in a formation flypast over the base. This happened during our camping holiday and was a very welcome surprise on my return, even if I had missed the fun myself.